Beauty is Not a Luxury

How American Founding Father John Adams misunderstood the value of art.

A friend recently reminded me of something John Adams wrote about art, in a letter he sent from Paris to his wife Abigail in 1780. The quote became an earworm irritating my mind for the past few weeks:

Since my Arrival this time I have driven about Paris, more than I did before. The rural Scenes around this Town are charming. The public Walks, Gardens, &c. are extremely beautifull. …

To take a Walk in the Gardens of the Palace of the Tuilleries, and describe the Statues there, all in marble, in which the ancient Divinities and Heroes are represented with exquisite Art, would be a very pleasant Amusement, and instructive Entertainment , improving in History, Mythology, Poetry, as well as in Statuary. Another Walk in the Gardens of Versailles, would be usefull and agreable.—But to observe these Objects with Taste and describe them so as to be understood, would require more time and thought than I can possibly Spare. It is not indeed the fine Arts, which our Country requires. The Usefull, the mechanic Arts, are those which We have occasion for in a young Country, as yet simple and not far advanced in Luxury, altho perhaps much too far for her Age and Character.

I could fill Volumes with Descriptions of Temples and Palaces, Paintings, Sculptures, Tapestry, Porcelaine, &c. &c. &c.—if I could have time. But I could not do this without neglecting my duty. The Science of Government is my Duty to study, more than all other Sciences: the Art of Legislation and Administration and Negotiation, ought to take Place, indeed to exclude in a manner all other Arts.—I must study Politicks and War that my sons may have liberty to study Mathematicks and Philosophy. My sons ought to study Mathematicks and Philosophy, Geography, natural History, Naval Architecture, navigation, Commerce and Agriculture, in order to give their Children a right to study Painting, Poetry, Musick, Architecture, Statuary, Tapestry and Porcelaine.

When I first read this quote many years ago, I appreciated that one of America’s Founding Fathers felt duty-bound to make sacrifices so that future generations may enjoy a fuller life. But these are harsh words for the arts, which Adams slandered as relatively frivolous. He made the wrong sacrifice.

Winston Churchill understood the value of beauty better than John Adams did. Churchill was memorably misquoted by the Village Voice as rejecting a suggestion by a member of Parliament to suspend arts funding during World War II by demanding to know “Then what are we fighting for?” Though apocryphal, this quote is directionally true to what Churchill actually said about art in an address to the Royal Academy in 1938, on the eve of war:

The Arts are essential to any complete national life. The State owes it to itself to sustain and encourage them…. Ill fares the race which fails to salute the arts with the reverence and delight which are their due.

Churchill said that art is essential and valuing beauty is our duty; Adams said that art is a luxury and beauty is a waste of time until more important matters have been studied. Then again, in the same year that Adams wrote his letter to Abigail, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts ratified its state constitution, which was principally drafted by Adams. In it, he penned a section titled “The Encouragement of Literature, &c.” to explain how the state government should promote education, science, and the arts. Adams also encouraged the formation of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences that Massachusetts chartered in 1780. So he couldn’t have meant that he literally had no time to spare for art — at the very least, he cared about building state institutions “to sustain and encourage” the arts as Churchill admonished, even if Adams didn’t expect those institutions to mature until his grandchildren’s time.

There’s also a whiff of utopia in the vision of progress that Adams laid out in his letter that seems incongruous with his worldview. He was a principal architect of the American system of checks-and-balances in government, because he believed that whenever people “felt themselves secure in the possession of their power” they “would begin to abuse it,” and therefore “Without three divisions of power, stationed to watch each other, and compare each other’s conduct with the laws, it will be impossible that the laws should at all times preserve their authority and govern all men.” This understanding of humanity as innately corrupt, and therefore in need of a system to restrain our vices, is hardly utopian.

But in his letter, Adams confidently assumes that children will remember the lessons their parents drew from studying politics and war. He seems optimistic that he had identified an incentive structure to free future generations from the need to explore weightier topics. And when he wrote about balanced government, he expressed a hope that the American people were “too enlightened” to undermine checks-and-balances. It’s as if Adams could only meet Kant halfway, and only agree with the first half of the philosopher’s famous quip that “Out of the crooked timber of humanity, no straight thing was ever made.” Adams accepted that humanity is crooked, but I wonder if he believed that he could straighten us out with his ideas for American governance.

Contrast this idealism to how political scientist Francis Fukuyama predicted the children of liberal democracy would behave in his 1989 essay (later expanded into a book) “The End of History?”. By this phrase, Fukuyama meant:

“History” with a capital H—what you could today call modernization or development. And the “end of history” was not about a termination of historical events, but more about where that historical process was going.

So the premise was basically trying to raise the question of progress: You know, are we making progress in human civilization? And if so, in what direction is that movement tending?

And at that time, my argument was that for 150 years, most progressive intellectuals thought — along with Karl Marx — that at the end of history there would be some form of communism. Marx says that quite explicitly. My observation was that it sure didn’t look like we would ever get there, and that if we were tending towards any final outcome, it would look more like a liberal democracy connected to a market economy. That was the argument, anyway.

I didn’t see a superior form of social organization over the horizon that we were still aspiring to — but it didn’t mean that all existing political systems were great or perfect.

And Fukuyama had concluded his 1989 piece on this glum note:

The end of history will be a very sad time. The struggle for recognition, the willingness to risk one’s life for a purely abstract goal, the worldwide ideological struggle that called forth daring, courage, imagination, and idealism, will be replaced by economic calculation, the endless solving of technical problems, environmental concerns, and the satisfaction of sophisticated consumer demands. In the post-historical period there will be neither art nor philosophy, just the perpetual caretaking of the museum of human history. I can feel in myself, and see in others around me, a powerful nostalgia for the time when history existed. Such nostalgia, in fact, will continue to fuel competition and conflict even in the post-historical world for some time to come. Even though I recognize its inevitability, I have the most ambivalent feelings for the civilization that has been created in Europe since 1945 with its north Atlantic and Asian offshoots. Perhaps this very prospect of centuries of boredom at the end of history will serve to get history started once again.

Fukuyama predicted that art would become improbable once liberal democracy progressed into boredom at “the end of history”; Adams asserted that liberal democracy must progress through a couple generations of learning to justify art. But if Adams misplaced his faith in us to use our freedom wisely, then his prescription would defer art indefinitely. What if the moment we earn the right to study art, we just get bored and restart history instead?

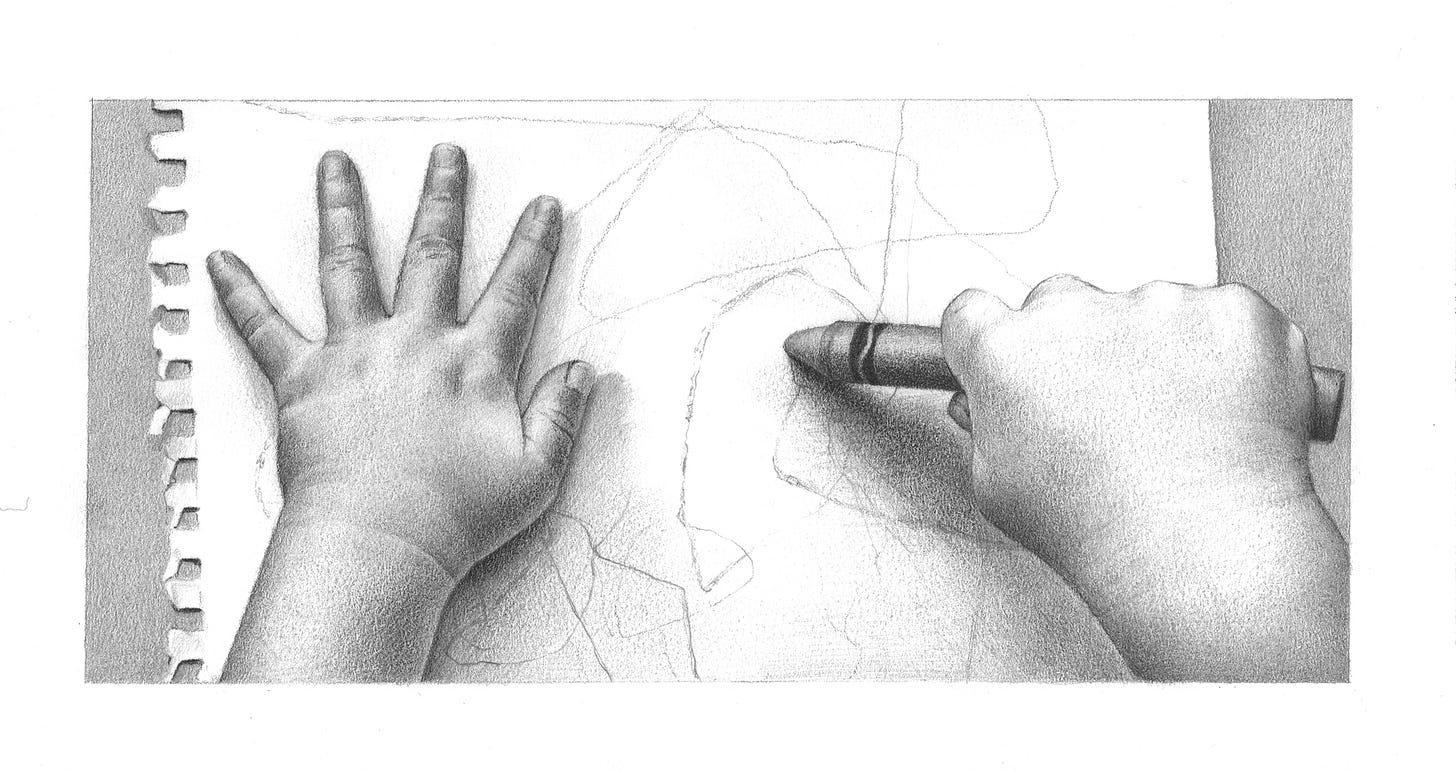

Human history is an extended atrocity, and yet all throughout we have created beautiful paintings and poems. Should we have waited millennia until John Adams and his compatriots came up with the American system of government? And why didn’t we? Why has humanity felt compelled to paint for tens of thousands of years, even while living under conditions that modern man would find obscene? That suggests to me that painting has been useful to humanity for an incomprehensibly long time — it is not just a luxury.

I write often about the value of art and beauty, and a couple of my go-to examples come from Viktor Frankl, who was a Holocaust survivor and psychologist, and Arthur Danto, who was a philosopher of aesthetics and an art critic. Both men treated beauty as a higher value in a way that may strike some as old-fashioned today. And both of them emphasize that beauty and art take on great importance in dark times.

In his 1946 memoir Man’s Search for Meaning, Frankl recalled how concentration camp prisoners would rush out of their huts to glimpse a sunset reflected in muddy puddles and whisper to each other of their awe at the world’s capacity for beauty. They “were carried away by nature’s beauty” and “experienced the beauty of art and nature as never before.” Frankl also described how listening to a symphony can give us a reason to live — and I urge anyone skeptical about the value of beauty to contemplate the significance of a Holocaust survivor describing beautiful art as a reason to live.

Despite his training as a philosopher of aesthetics, Danto didn’t discover the value of beauty until he was pushing 80. In his 2003 book The Abuse of Beauty, Danto admits that he initially “felt somewhat sheepish about writing on beauty” which “had almost entirely disappeared from artistic reality in the twentieth century, as if attractiveness was somehow a stigma, with its crass commercial implications.” It took one of the most brazen terrorist attacks in history for him to realize that beauty matters, when “The spontaneous appearance of those moving improvised shrines everywhere in New York after the terrorist attack of September 11th, 2001, was evidence for me that the need for beauty in the extreme moments of life is deeply ingrained in the human framework.” That’s when he finally realized that “beauty is the only one of the aesthetic qualities that is also a value, like truth and goodness. It is not simply among the values we live by, but one of the values that defines what a fully human life means.”

Both pretentious art world insiders and John Adams have treated beauty as unserious. And at times, beauty can be appropriated for saccharine purposes. The same sunset that sustained the souls of concentration camp prisoners may also be printed on a sappy Hallmark card or painted into the background of a kitschy Thomas Kinkade painting. But these tacky representations do not detract from the beauty of a real sunset. They show us what it looks like when someone has not depicted beauty eloquently.

Artists are responsible for summoning more beauty into the world. They have a duty to enrich humanity just as John Adams had a duty to begin the American experiment. In dark times, masterful artists can give people a reason to live, and at the end of history, artists must try to resist apathy. Imagine if we could summon enough new beauty into the world to divert people from boredom and help prevent us from restarting history. Even if we fail, the beauty we create will sustain us in the dark times ahead once history begins again.

This is a great piece. I'll restack it later on.