Liberalism as the Shining City on a Hill

Why we all need to read Benny Morris

This visual essay first appeared in Quillette on May 3, 2025. I regularly contribute visual essays to Quillette that spotlight pieces from the magazine’s archive.

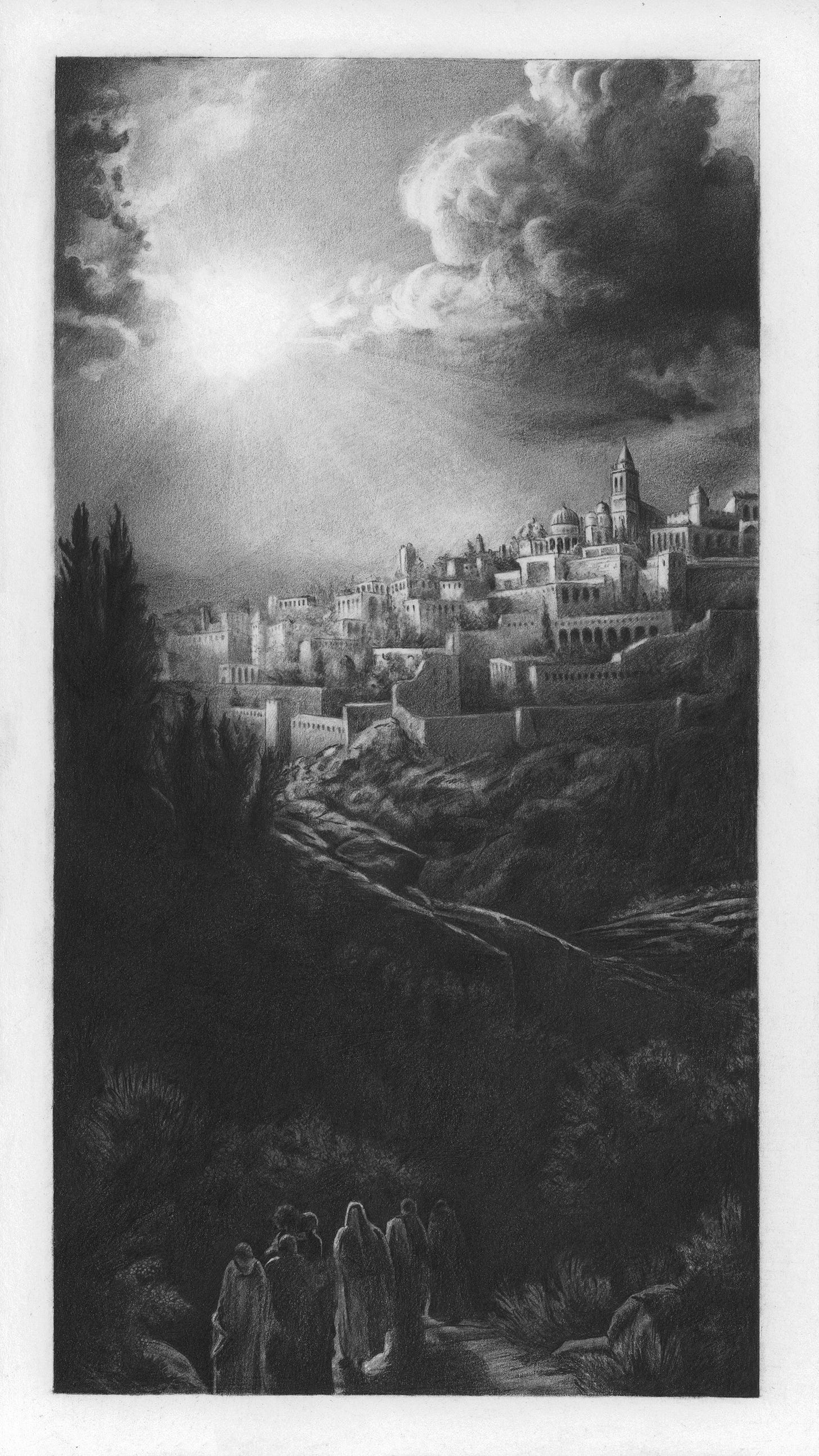

For almost 300 years, America has cultivated the metaphor of a shining city on a hill to describe how a righteous society is a beacon for a better life—but the same light casts that city under a glare, exposing its defects. The image comes from Jesus speaking to his followers in the Book of Matthew (5:14), “You are the light of the world. A city on a hill cannot be hidden.” When the Puritans departed England for Boston in 1630, their leader John Winthrop used the metaphor to warn them that “the eyes of all people are upon us,” as they set forth to establish a new community.

Two hundred years later, when Alexis de Tocqueville chronicled American democracy in the 1830s, he asserted that these early colonists “brought to the New World a Christianity that I cannot depict better than to call it democratic and republican,” for “[n]ext to each religion is a political opinion that is joined to it by affinity.” Twentieth-century American presidents like John F. Kennedy, Ronald Reagan, and Barack Obama made a habit of referencing the shining city in speeches, especially when visiting Massachusetts, to define America as a lighthouse for liberalism. In Australia, the variation “the light on the hill” was used in a 1949 speech by Prime Minister Ben Chifley.

The image of a shining city on a hill encapsulates the optimistic vision that free, open societies will thrive and spread as the world converts to liberal democracy. But it comes with a warning: The same torch that beckons the huddled masses toward Lady Liberty also illuminates the shame of liberal democracies that betray their values. Because the light symbolises righteousness, every failing is an indication of hypocrisy. And like women inspecting their pores under the cool glow of LED-rimmed mirrors, each blemish can make citizens of liberal democracies more neurotic—while clever dictators shroud themselves in mood lighting.

If the story of the twentieth century was that of liberalism overcoming totalitarianism, then the question facing the twenty-first century is whether that win is durable. Liberalism likely needs the self-esteem expressed in a belief that it is a shining city on a hill to withstand whataboutism from its repressive and violent competitors. Its people need to fix problems rather than fixate on them, so that when citizens of liberal democracies feel as though they’re standing under harsh fluorescents, it is because they are like surgeons stitching wounds—not pathologists conducting autopsies.

Admittedly, right now it feels as if the American-led liberal order is haemorrhaging on the operating table. It has been compromised by President Donald Trump curtailing alliances and trade with nearly every other liberal democracy—except perhaps one. “Publicly, Benjamin Netanyahu and his supporters continue to paint Trump as a staunch, irreproachable supporter of Israel,” wrote the Israeli historian Benny Morris for Quillette last month:

They point to the fact that, during his first term as president, he transferred the US Embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, as Israel had long demanded, and remind people that he helped facilitate the Abraham Accords of the early 2020s, which normalised the Jewish State’s relations with Bahrain, the United Arab Emirates, Morocco, and even Sudan. And in recent weeks, he revoked his predecessor Joe Biden’s suspension of certain weapons shipments to Israel, including 2,000-pound (907 kg) aerial bombs and 155 mm artillery shells.

But serious doubts remain as to Trump’s commitment to the “special relationship” between Washington and Jerusalem, especially in view of his apparent abandonment of Ukraine and his very public efforts to distance the United States from its traditional commitments to European security.

Morris explains that the special relationship is “based on shared values like support for democracy” and that it “predates even the establishment of Israel itself in May 1948.” From the American perspective, many people understand the very existence of Israel as a consequence of the twentieth-century battle between liberalism and totalitarianism, and they learn about Israeli history as a sequel to the Holocaust story. More broadly, citizens from all countries that once liberated Nazi concentration camps have incorporated their grandfathers’ heroism into their national identities so that the outcome of the Holocaust story is pivotal to how people in all liberal democracies think of themselves.

This includes Israelis. For David Ben-Gurion, the “founding father” and first prime minister of Israel, the Jewish State was meant to be “a light unto the nations.” This formulation comes from the book of Isaiah (49:6), “I will also make you a light for the nations, that my salvation may reach to the ends of the earth.”

W.E.B. Du Bois saw Israel’s potential and urged his fellow Americans to help the aspiring country, writing that it was “not a difficult question.” He became an early supporter of Israel after he saw the flattened Warsaw ghetto. It taught him that his previous framework for understanding race relations had been provincial, restricted as it was to conflicts between black and white. He writes:

I have been to Poland three times. The first time was 59 years ago, when I was a student at the University of Berlin. I had been talking to my schoolmate, Stanislaus Ritter von Estreicher. I had been telling him of the race problem in America, which seemed to me at the time the only race problem and the greatest social problem of the world. He brushed it aside. He said, “You know nothing, really, about real race problems.” …

I was astonished; because race problems at the time were to me purely problems of color, and principally of slavery in the United States and near-slavery in Africa. …

The result of these three visits, and particularly of my view of the Warsaw ghetto, was not so much a clearer understanding of the Jewish problem in the world as it was a real and more complete understanding of the Negro problem. In the first place, the problem of slavery, emancipation, and caste in the United States was no longer in my mind a separate and unique thing as I had so long conceived it. It was not even solely a matter of color and physical and racial characteristics, which was particularly a hard thing for me to learn, since for a lifetime the color line had been a real and efficient cause of misery. So … the ghetto of Warsaw helped me to emerge from a certain social provincialism into a broader conception of what the fight against race segregation, religious discrimination and the oppression by wealth had to become if civilization was going to triumph and broaden in the world.

Du Bois describes liberalism as having the impact of the shining city on a hill—a “civilization… to triumph and broaden in the world.” He imagined Israelis as fellow dreamers about the freedom that liberalism has to offer. But now, 75 years later, many Americans who think they continue his legacy, like Ta-Nehisi Coates, compare Israel to the villains from the Jim Crow era that Du Bois lived through.

And so, the only liberal democracy not yet alienated by President Trump is viewed with suspicion by many Americans, and plenty of others in the Western world. Though all liberal democracies are frequently subjected to scrutiny, only Israel is strip-searched. Leading up to 7 October 2023, it became fashionable among some liberals to call Gaza an open-air concentration camp. But if it is true that even the grandchildren of Holocaust survivors can grow up to behave like Nazis, then that implies that liberalism itself is a precarious condition—that lofty ideals will dim once our inner demons inevitably overcome the better angels of our nature. And that perhaps human nature is not honourable enough to keep us faithful to our enlightened ideals for very long.

For those of us who cherish liberalism as a philosophy, it can feel imperative that Israel succeed in living up to our ideals, to give our Holocaust story the right ending. And so the West obsesses over Israel; perhaps no other topic inflames tempers and attracts propaganda merchants as much as the twinned fates of Israel and Palestine. It is hard to find information on the subject that is uncontaminated by prejudice.

One heuristic for discerning who aims at the truth is finding those willing to critique their own side of the argument—this is a terrific challenge, for it is human nature to fear that criticising one’s own side will simply give succour to one’s enemies. We can use this metric to help distinguish whether someone is partisan or principled. The principled person is an emissary from the shining city on a hill, in an information landscape suffering from a blackout.

One such emissary is Israeli historian Benny Morris. In 1988, he coined the term “New Historians” to describe writers like himself, who set out to clarify their country’s story. Pulitzer Prize winning journalist Ethan Bronner has summarised their influence in a 2003 New York Times piece:

Dismissed at first as self-haters and even traitors, the new historians gained respect during the 1990’s—so much so that a 1998 series on state television to mark Israel’s 50th anniversary borrowed considerably from their work, as did ninth-grade textbooks introduced the following year.

History does not get written or read in a vacuum. The new historians had an agenda—promoting the peace process then beginning. And many Israelis, eager to put an end to their century-old conflict, were willing to be told that their successful nation building had come at a high cost to the Palestinians. They were adjusting their collective narrative to make room for coexistence with onetime enemies.

Morris expresses this stance in his first essay for Quillette, where he shares the story of his military jail-time in Israel. He served in the Israel Defence Forces (IDF) for over twenty years, first as a conscript and later as a reservist, and during that time spent three stints in jail. The first two incidents were humorous and inconsequential wrist slaps for acting like a “miscreant,” as Morris describes his younger self, but he writes that “the third and last incarcerative episode was the most serious, and no joking matter”:

I refused to take part in the suppression of the First Intifada, which had broken out the previous December …. The platoon and company commanders tried to dissuade me. I stuck to my guns. …

“What we are doing is wrong; a crime,” I said.

“You leave me no choice,” [my commanding officer] replied. “I’ll have to send you to prison. And believe me, it’s not for you, you’re a journalist, a doctor [of history].” (A few months before, I had published my first book, The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem, 1947–1949.)

“I also have no choice. We have to get out of the territories.”

“Even if I agree with you, in the army we must carry out orders. It’s not a matter of political beliefs. I sentence you to 21 days in jail,” he concluded. …

Prison Number 4 would not take in new inmates during the weekend. So I spent it in a tent with a quartermaster who had been denied leave for some offense or other. He was of North African origin and his hard line was typical of Israel’s Mizrahi Jews. “The only way to end the Intifada is to hit them hard, with an iron fist. It’s the only language they understand. If you speak to them and act softly, they think you are weak, they will exploit you. Be tough, and they’ll respect you,” he said.

While he was imprisoned for his conscientious objection, Morris got into an argument with a fellow prisoner who believed the kinds of things that Israel’s critics and enemies often suspect of Israelis:

“They should have given you a year, not 21 days. We should kill all of them [i.e., the Arabs]. Stand them up against a wall and shoot them.” He takes aim with his arm, spraying the wall with gunfire. “We should do to them what Hitler did to us. Because that’s what they want to do to us. And you guys, you Peace Now-niks and leftists, you’re working for them, for the PLO. As it says in the Bible, ‘thy destroyers and they that made thee waste shall go forth out of thee.’” (Isaiah 49:17) It was all very public. During the discussion—more accurately, his rant—prisoners gathered around us. They clearly agreed with Darwish. There was a feeling of mob violence in the air. But nothing happened.

A lesser man would have left that part out of his story to help his side of the conflict save face.

In the coming years, both Morris and the Israeli–Palestinian conflict would change. When the far more vicious Second Intifada began about a decade later, Morris opposed conscientious objection. In 2004, towards the end of the Second Intifada, he gave an interview to Ari Shavit in Haaretz. Shavit prefaces the interview by splitting Morris into two personalities: historian Morris, “the great documenter of the sins of Zionism,” and citizen Morris, who “in fact identifies with those sins … he thinks some of them, at least, were unavoidable.”

Shavit sets the scene: “The researcher who was accused of being an Israel hater (and was boycotted by the Israeli academic establishment) began to publish articles in favor of Israel in the British paper The Guardian.” At the same time, Morris continued publishing new evidence of Israeli war crimes, including frequent rape, from their 1948 war with the Palestinians. Shavit probes Morris to understand how the historian reconciles his exceptional compassion for Palestinian suffering with his unapologetic Zionism, and how the Second Intifada altered his point of view.

Their exchange is breathtakingly blunt:

Shavit: Benny Morris, for decades you have been researching the dark side of Zionism. You are an expert on the atrocities of 1948. In the end, do you in effect justify all this? Are you an advocate of the transfer of 1948?

Morris: There is no justification for acts of rape. There is no justification for acts of massacre. Those are war crimes. But in certain conditions, expulsion is not a war crime. I don't think that the expulsions of 1948 were war crimes. You can’t make an omelet without breaking eggs. You have to dirty your hands.

Shavit: We are talking about the killing of thousands of people, the destruction of an entire society …. They perpetuated ethnic cleansing.

Morris: There are circumstances in history that justify ethnic cleansing … when the choice is between ethnic cleansing and genocide—the annihilation of your people—I prefer ethnic cleansing.

Shavit: And that was the situation in 1948?

Morris: That was the situation. That is what Zionism faced. A Jewish state would not have come into being without the uprooting of 700,000 Palestinians. Therefore it was necessary to uproot them. There was no choice but to expel that population. It was necessary to cleanse the hinterland and cleanse the border areas and cleanse the main roads. It was necessary to cleanse the villages from which our convoys and our settlements were fired on.

Shavit: The term “to cleanse” is terrible.

Morris: I know it doesn’t sound nice but that’s the term they used at the time. I adopted it from all the 1948 documents in which I am immersed.

The connotations of “ethnic cleansing” are more powerful than the definition, on which none agree. But Morris refuses to pussyfoot around phrases just because they elicit disgust and opprobrium—elsewhere in the interview, he explains that compared to other nations’ wars, Israel only committed “small war crimes” in 1948. Whatever this bald language may cost Morris in diplomacy is compensated by the credibility it gives him as a straight talker. People can condemn him for his beliefs, but he clearly came by them honestly. He seems immune to any temptation to sugarcoat the Israeli side of the story.

When Shavit asks Morris if he would advocate a population transfer in the future, the historian answers that it would only be justified in an apocalyptic situation. Morris also explains that his views changed at the turn of the century, after diplomacy had repeatedly failed. The violence of the Second Intifada convinced him that the Palestinians “are unwilling to accept the two-state solution. They want it all.” Similarly, in his 2003 New York Times piece, written during the Second Intifada, Bronner notes that:

There were virtually no Palestinian “new historians” asking whether their leader in the 1930’s and 40’s, Haj Amin al-Husseini, was right to collaborate with the Nazis, calling for the killing of Jews “wherever you find them.” Few Muslim leaders questioned whether sending suicide bombers into Israeli cafes was a moral act. No Arab television station ran a series on David Ben-Gurion’s confrontation with rebel Zionist militias. Israel’s new historians were viewed by Arab intellectuals not as an invitation to self-examination but as further evidence that Zionism was a crime. Worst of all, in 2000, when Israel offered Yasir Arafat more than 90 percent of the occupied West Bank and Gaza Strip for a Palestinian state, his rejection was accompanied by a terrorist war that shows no signs of stopping.

Morris clarifies that he still supports a two-state solution ideologically, because it is the most humane outcome. But he predicts that there will be no peace in either his lifetime or for the next generation:

Shavit: Aren’t your harsh words an over-reaction to three hard years of terrorism?

Morris: The bombing of the buses and restaurants really shook me. They made me understand the depth of the hatred for us. They made me understand that the Palestinian, Arab and Muslim hostility toward Jewish existence here is taking us to the brink of destruction. I don’t see the suicide bombings as isolated acts. They express the deep will of the Palestinian people. That is what the majority of the Palestinians want. They want what happened to the bus to happen to all of us.

Shavit: Yet we, too, bear responsibility for the violence and the hatred: the occupation, the roadblocks, the closures, maybe even the Nakba itself.

Morris: You don’t have to tell me that. I have researched Palestinian history. I understand the reasons for the hatred very well. The Palestinians are retaliating now not only for yesterday’s closure but for the Nakba as well. But that is not a sufficient explanation. The peoples of Africa were oppressed by the European powers no less than the Palestinians were oppressed by us, but nevertheless I don’t see African terrorism in London, Paris or Brussels. The Germans killed far more of us than we killed the Palestinians, but we aren’t blowing up buses in Munich and Nuremberg. So there is something else here, something deeper, that has to do with Islam and Arab culture.

Israel is the only liberal democracy in the Middle East, and, as Morris points out, the fundamental problem for the Jewish State is that it is located within an illiberal and tribal part of the world where, Morris believes, “human life doesn’t have the same value as it does in the West, in which freedom, democracy, openness and creativity are alien.” Though he believes that Western liberalism is strong, he is unsure whether Western liberals understand how to “repulse this wave of hatred.” He frames the conflict between Israel and Palestine as “a clash between civilizations” that threatens liberal democracy everywhere. He tells Shavit,

Morris: Yes. I think that the war between the civilizations is the main characteristic of the 21st century …. It’s not only a matter of bin Laden. This is a struggle against a whole world that espouses different values. And we are on the front line. …

Shavit: … You are not entirely convinced that we can survive here, are you?

Morris: The possibility of annihilation exists.

We are reading this interview about twenty years after Morris and Shavit spoke, while every liberal democracy in the world has been embroiled in protests over the Israel–Hamas war. Morris’s perspective suggests that the unrest is global because Israel is “on the front line” of an international war of ideas and values.

Reading Benny Morris can help the West comprehend the inescapable savagery of this conflict. He embraces the complexity that undiscerning polemicists like Ta-Nehisi Coates reject. Morris recently lambasted Coates’ The Message in his Substack newsletter Benny Morris’s Corner:

In “The Message” Coates zooms in on Israel’s ills: The minority of extreme right-wingers and Kahanists—like Israel’s former national security minister, Itamar Ben-Gvir, who honors, indeed adulates, murderers like Baruch Goldstein, who mowed down 29 Arab worshippers in a Hebron mosque in 1994—and their deeds and pronouncements. The inexpert reader will come way from “The Message” with the impression that that is Israel. “Goldstein has won,” he tells us. And maybe down the road he will. But he hasn’t yet and maybe he won’t. And certainly this wasn’t the picture during most of Israel’s lifetime. Wokists may not pardon me, but I still believe that Ehud Barak hit the nail on the head when he described Israel as “a villa in the jungle.” Coates, after a ten-day junket spent mostly among Arabs and in the occupied territories, and reinforced by selective reading, mostly by Israel-haters, is essentially ignorant. A little modesty is perhaps in order, even by a person perched on the Sterling Brown Endowed Chair in the English Department of Howard University.

Morris has published numerous essays in Quillette, many of which offer commentary on the current Israel–Hamas war. Consistent with his longstanding practice, these essays do not shy away from painful truths, even when they implicate Morris’s own side. For example, in the piece, “Benjamin Netanyahu, Would-Be Authoritarian,” Morris argues that the Israeli leader has been trying to “concentrate power in his hands” to “allow him to undermine free speech and the rule of law in Israel.”

Morris explains how the Prime Minister has tried to wrest control of the Israeli Supreme Court; how he has allied himself with extremists who allow (or even encourage) “West Bank settlers to harass and terrorise their Arab neighbours”; how the police under Netanyahu’s tenure have increased surveillance of Arab Israeli citizens, so that “freedom of expression of Israel’s Arabs has been severely curtailed.” Clearly, Morris has not become a nationalist yes-man.

Some of Morris’s other Quillette essays directly confront falsehoods about Israel. After the New York Times published an erroneous primer on the 1948 war—a topic Morris covers in detail in his 2009 tome 1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War—he wrote a comprehensive rebuttal to their “welter of factual errors and misleading judgments.” Where the Times obfuscates with the passive voice and lies of omission, Morris assigns agency and makes history explicit. As he writes:

the article’s worst historical distortions concern the events surrounding the Second World War. [Derek] Penslar claims that “between 9,000 and 12,000 Palestinians fought for the Allied forces in World War II.” In fact, as far as I know, it is doubtful whether any Palestine Arabs actually “fought” during the war, though perhaps some 6,000 of Palestine’s 1.2 million Arabs signed up with the British and served as cooks, drivers, or guards in British installations in Palestine. By comparison, around 28,000 of Palestine’s Jews—out of a population of around 550,000—joined the British army, and many of them actually fought in North Africa and Italy in 1941–1945.

This talk of Palestine Arabs “fighting” alongside the British is, at best, misleading. Palestine’s Arabs—like most of the Middle East’s Arabs—would have preferred a Nazi German victory and the defeat of the Western democracies. The British were seen as the common enemy of the Germans and the Palestinians. As Sakakini, a Palestinian nationalist, relates in a diary entry of 1941, the Arabs of Palestine “had rejoiced when the British bastion at Tobruk fell to the Germans,” and “not only the Palestinians rejoiced … but the whole Arab world.”

This support for Hitler wasn’t merely a matter of the old adage that “my enemy’s enemy is my friend.” Muhammed Amin al-Husseini, the leader of the Palestine national movement, was an outspoken antisemite. He aided the 1941 pro-Nazi revolt in Baghdad. When it collapsed, he fled to Berlin, where he spent the rest of the war years enjoying a handsome salary for his work as a Nazi propagandist and a recruiter of Balkan Muslims for the SS.

Palestine’s Arabs thus assisted in the destruction of European Jewry in two ways: They successfully pressured the British into closing the gates of Palestine to European Jews fleeing the Holocaust; and they supported Germany’s efforts to win the war. In radio broadcasts from Berlin, Husseini called on the Arab world to rebel against Britain and “kill the Jews.”

Similarly, in “Tragedy and Half-Truths: A Gaza Diary,” Morris describes how Atef Abu Saif’s 2024 book Don't Look Left “provides a vivid account of the horrors of daily life in the Gaza Strip, yet omits to mention Hamas’s role in the war.” Morris unflinchingly acknowledges how much misery the war, including Israel’s attacks, has inflicted. In Saif’s memoir, “Death haunts every page; everyone lives in fear that today might be his last.” Compassion is important—but so is historical accuracy. He writes:

But why the ongoing tragedy of the 2023–24 war in Gaza came to pass—at least, its immediate context—is completely elided in the book’s 280 pages, which renders the work, however accurate and moving in its details, a piece of propaganda. Completely absent from its pages are the Hamas fighters and their brothers in the smaller Islamic Jihad organisation, who, in a surprise attack on 7 October 2023, invaded southern Israel and murdered 850 civilians, raped countless women, and took some 250 Israelis hostage—most of them civilian men, women, and children ranging in age from a few months old to octogenarians—and killed some 360 IDF soldiers, while they destroyed most of the border-hugging kibbutzim with their peace-loving, left-wing inhabitants. Yet it is that assault that triggered the devastating Israeli response, now in its eleventh month.

Incredibly, the word “Hamas” appears only twice in the book and Hamas fighters, whether alive, wounded, or dead—and, according to the IDF some 15–20,000 of them have died so far—are nowhere mentioned, not once.

The West won’t be so easily misled if more liberals read Benny Morris. And given the potentially moribund state of the American-led liberal order, becoming genuinely knowledgeable about this conflict is imperative. If we take liberalism seriously as the best ideology humanity has yet mustered, then it is our duty to champion that position on the world stage.

Israel may not survive without US support, as a tiny country on the frontier of liberal democracy that has always depended on American military aid to fend off the enemies that encircle it. We should worry with Morris about the possibility of its annihilation. Given that US support for every liberal democracy has become unpredictable, the rest of the West must find enough self-esteem to defend liberal values and liberal states while America gets its house in order. For too long, the status quo for “good liberals” in the West has been self-depreciating cynicism about the virtues of the free world. This is a cowardly position that shrinks from the challenge of never making the perfect the enemy of the good.

Liberals don’t like to think of themselves as the kind of people who wage war; it is not gunfire that lights up the shining city. But come what may for this vexed conflict, liberal democracies can neither allow their adversaries to define them with bad-faith accusations nor compromise on their commitment to self-examination. And they have the best tool on hand for finding this clarity: enough light for those who have eyes to see.

This is an extraordinarily well written piece. My concern is that neither of the powers that be for either side are interested in a two nation solution. This is a dream of those in the west who want to see an end to this quagmire. For Arabs/Muslims this is not about Palestine , but rather destroying Israel and to that there is no end. I just do not see a peaceful solution and that's depressing.

Friends just explained to me that the Soviet Union was the essential backer of Israel's founding and primary source of weapons and other resources for its war of Independence. The story goes that Stalin hated Jews and welcomed a vehicle to remove them from Soviet territory. Israel's socialist history is of course well known.

I found all of this very funny because today, Israel's biggest attractors are far lefties and socialists, depending on how you count right-wing anti-semites. My understanding is that the USSR turned against Israel when it became a strong liberal democracy and, wait for it, shining city on a hill, in a region of poverty and authoritarianism.

I wish substack comments autosaved!