On the Value of Drawing

Humans have been drawing for tens of thousands of years for good reason.

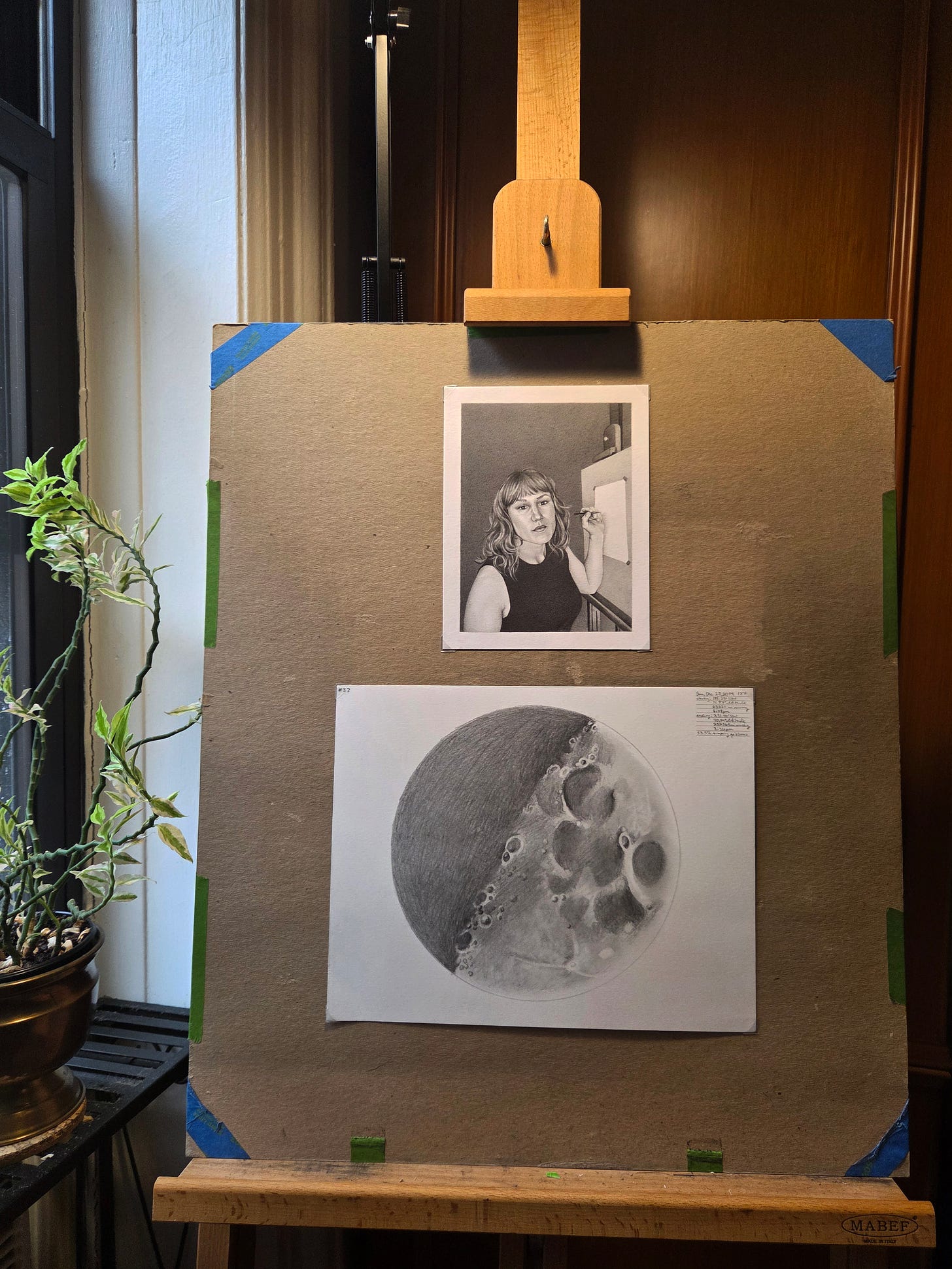

Two of my recent essays are about the value of drawing: “Learning How To See The Moon” in Drawing Never Dies and “The Power of Art in the AI Age” for The Metropolitan Review (this one is also about the relationship between art and technology, and between Romanticism and the Enlightenment).

I wrote these pieces back to back, so that the first one felt like a prelude to the second. And they’re best read as a pair, which is why I want to weave them together here. “Learning How To See The Moon” elaborates on a key point I made in “The Power of Art in the AI Age” about the difference between how a camera and an artist see the world:

This is what it means to see great art and think, “That looks like a Friedrich painting,” rather than, say, a Degas. Even if Friedrich and Degas had painted the same scene, their equally accurate observations would not yield identical paintings like replicable scientific studies, because their styles are singular. Merely good artists cannot transcend imitation to paint pictures so uniquely their own. Those who fall just shy of the mark become the second-rate painters captured in the orbit of great artists, amplifying their styles into full-blown art movements until history forgets them.

This is one reason why the camera could never truly replace drawing and painting for artists, whereas it made sense for scientists to stop relying on naturalist drawings once photography provided a more objective way to make pictures. Artists never needed to react to photography by rejecting naturalistic representation or traditional skills, because cameras cannot observe reality with the same subjective lens that artists see through. These were never interchangeable ways of looking at the world.

In “Learning How To See The Moon,” I get at the same point — that a camera and an artist see quite differently — by explaining what I learned from spending six months drawing the moon every night:

Photography produces more accurate images, but it cannot teach you how to see nearly so well as observational drawing. Had I snapped a photo of the moon every night, then I could have never known it intimately — like how sex brings you far closer to another person than sharing a kiss.

I paired my own drawing experience with my observations from teaching drawing at universities for a decade:

You can take a photo in an instant but then hardly register all the information it contains, whereas observational drawing demands that you choose where to place each line and dot, repeatedly comparing reality to every square centimeter of the emerging image, then changing the drawing to better match what you are looking at. When I teach drawing, I explain to students that the process is like those puzzles in children’s coloring books that present two nearly identical pictures and ask you to spot ten subtle differences between them; except in observational drawing, as you spot discrepancies, you correct them. Even when students fail at realism, after spending hours carefully observing their subject, they see it more clearly than if they had snapped an accurate photo, and that clearer vision helps them draw better on their next attempt.

It would have been easier to draw the moon by looking at a photograph, where my fingers would have never stiffened from hours spent drawing outdoors on frosty nights. Photography does the hard work of flattening the moving, three-dimensional world into two static dimensions. This is how Photorealists, like the painter Chuck Close, held the world still long enough to recreate it as accurately as the photos their paintings were based on. Otherwise, even if drawing a still life that supposedly sits still, every time artists move their heads, they see their subject from a slightly different angle, and over the course of an hours-long drawing, light changes from morning to evening, shifting shadows and colors. Admiration for Photorealism stems largely from appreciating how keenly those painters observed their photographs, which is indeed masterful, but they did not have to grapple with what the Impressionist ringleader Claude Monet called “the most fugitive effects” of nature.

This is not to say that cameras cannot teach something. You must sharpen your powers of observation to become a good photographer, too. But cameras cannot give you the most advanced lessons in learning how to see — for that, you will need a pencil.

I worry that as image generation becomes easier and easier, people will have fewer incentives to learn how to draw. It seems probable that AI image generation will make a lot of illustration and design work obsolete, for one thing. As I wrote in “The Power of Art in the AI Age,” technology has democratized the ability to transcribe reality — once upon a time, only artists could take selfies.

And though I’m excited about AI overall, I grieve over a possible future with less people drawing in it. If you don’t know how to draw from observation, then you can’t see well. This became apparent to me as a teacher, when I had to figure out how to show my students things that I could see clearly, but they could not see at all. Often teaching would feel like pointing something out to a friend who can’t locate what your finger is indicating. There! Right there! Can’t you see it?! Just turn your head a little! Oh, come on, it’s right there!

How can you see beauty fully without clear vision? I feel so much pity for people who can’t draw. It seems tragic to go through life without being able to see all of the beauty that’s right before your eyes.

I don't play any instruments, so I know musicians must hear beauty inaccessible to me even though it's right before my ears!

Totally. I can't draw a thing and it's terrible! I suspect life is much better if you have this. Lovely piece!