When Curiosity Kills The Cat

On the lab leak theory of COVID-19 origins, and its effect on the value of science.

The mad scientist’s stench, a rich formaldehyde perfume carrying hints of latex gloves and undercurrents of ammonia, cannot be showered off “the lab leak theory.” Attempts at understanding the genesis of COVID-19 are shrouded in circumstantial evidence, and the laboratory origin hypothesis to explain it is controversial. Some have denounced it as anti-science. But if it turns out to be true, then Dr. Frankenstein’s monster will cast a lumbering shadow across millions of graves. The possibility that scientists produced this plague may throw the value of science into question.

I am something of a mad scientist myself. As such, my experience in disturbing people is relevant to this question about the value of science, and I would like to offer what insights I can. To start, what could compel someone to become a mad scientist?

Officially, I bill myself as an artist and have no formal training in the sciences, but when I learned that the internet could teach me how to build a subatomic particle detector, I packed up my paintbrushes. This was simply not the kind of thing one ought be able to do on her own, and that was reason enough to try. In due course, I had a working prototype set up in my art studio. By placing uranium ore inside of my machine, the subatomic world became visible, and I felt awe at perceiving the infinitesimal.

My colleagues felt disturbed and alarmed that I might give them radiation poisoning, or perhaps blow up their adjacent studios. I was fascinated at how a phenomenon that enchanted my imagination terrorized theirs, and this experience set me on a path of repurposing unsettling scientific materials to create artwork that commingles eeriness and elegance. I became something of a mad scientist because I wanted to grasp at the sublime — those encounters that inspire awe and angst in equal measure.

Just as my colleagues feared the byproducts of my art studio, proponents of the lab leak theory of COVID-19 origins fear the unintended consequences of virology research. Other pathogens have already leaked from labs, and reflecting on this history clarifies the reasons for concern.

A Brief History Of Lab Leaks

“Lab leak” is a broad phrase that encompasses any event that might release a pathogen from a laboratory, including but not limited to: accidental needle pricks, bites and scratches from laboratory animals, faulty air ducts, ruptured personal protective gear, broken latches on biohazard barrels, shipping the wrong samples outside of high security labs, shipping contaminated samples out of high security labs, simple spills. The vast majority of such incidents have been near misses that did not infect anyone, but over the past century or so, a few high-profile events sickened or killed swaths of innocent bystanders.1

An infamous lab leak occurred in 1979, when a Soviet military research facility accidentally released a plume of anthrax spores that infected about a hundred and killed at least 66 people, while also revealing that the Soviet Union was developing biological weapons. Fortunately, the wind carrying the anthrax plume did not blow towards the nearby city, where it may have infected hundreds of thousands of people. Notably, the true rate of infection and death was surely higher than these verified numbers, because the Soviets tried to cover up the accident.

What may be the largest confirmed laboratory accident in the history of infectious diseases occurred much more recently at a biopharmaceutical plant in Lanzhou, China, in July and August 2019, when the use of expired disinfectant led to the aerosolization of Brucella, a bacteria that causes a variety of symptoms and long term complications ranging from fever and fatigue to a swollen heart, sometimes resulting in death. Like the anthrax incident in the Soviet Union, wind carried the bacteria to unsuspecting victims, and a whopping 10,000+ people contracted brucellosis as a result of that lab leak. Gratefully, no deaths were reported despite an historic case fatality rate of 2%.

Coronaviruses are proven escape artists. In August 2003, a postdoctoral student at the National University of Singapore was infected with the first SARS virus, and an investigative panel concluded that “inappropriate laboratory standards and a cross-contamination of West Nile virus samples with SARS coronavirus in the laboratory led to the infection of the doctoral student.” Also in 2003, a senior scientist at the National Defense University in Taipei contracted SARS in a biosafety level 4 lab (the highest level of biosafety), probably from some spilled liquid the immunologist recalled seeing on the surface of a test tube that he handled without wearing gloves. Then in April 2004, a couple researchers at the Chinese Institute of Virology in Beijing contracted SARS in separate incidents a mere fortnight apart as a result of two distinct breaches of safety procedures, and spread the virus to seven other individuals — one of whom, the mother of the 26-year-old postgraduate student who was infected in the first laboratory incident, died from the SARS infection.

Since the current pandemic began, there has been a confirmed lab leak of the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19, as well. In November 2021, a research assistant at Academia Sinica in Taiwan contracted COVID-19 after handling infected animals. This was the world’s first documented infection with SARS-CoV-2 in a research lab. A December 2021 statement by an external investigation committee noted that staff involved in experiments at the lab did not wear appropriate personal protective gear, including N95 masks and gloves, or follow procedures for the safe use of lab equipment. The academy was fined, the infected lab worker voluntarily resigned, and her boss (who was the aforementioned immunologist that got infected with SARS in Taipei after touching a spill without gloves) retired.

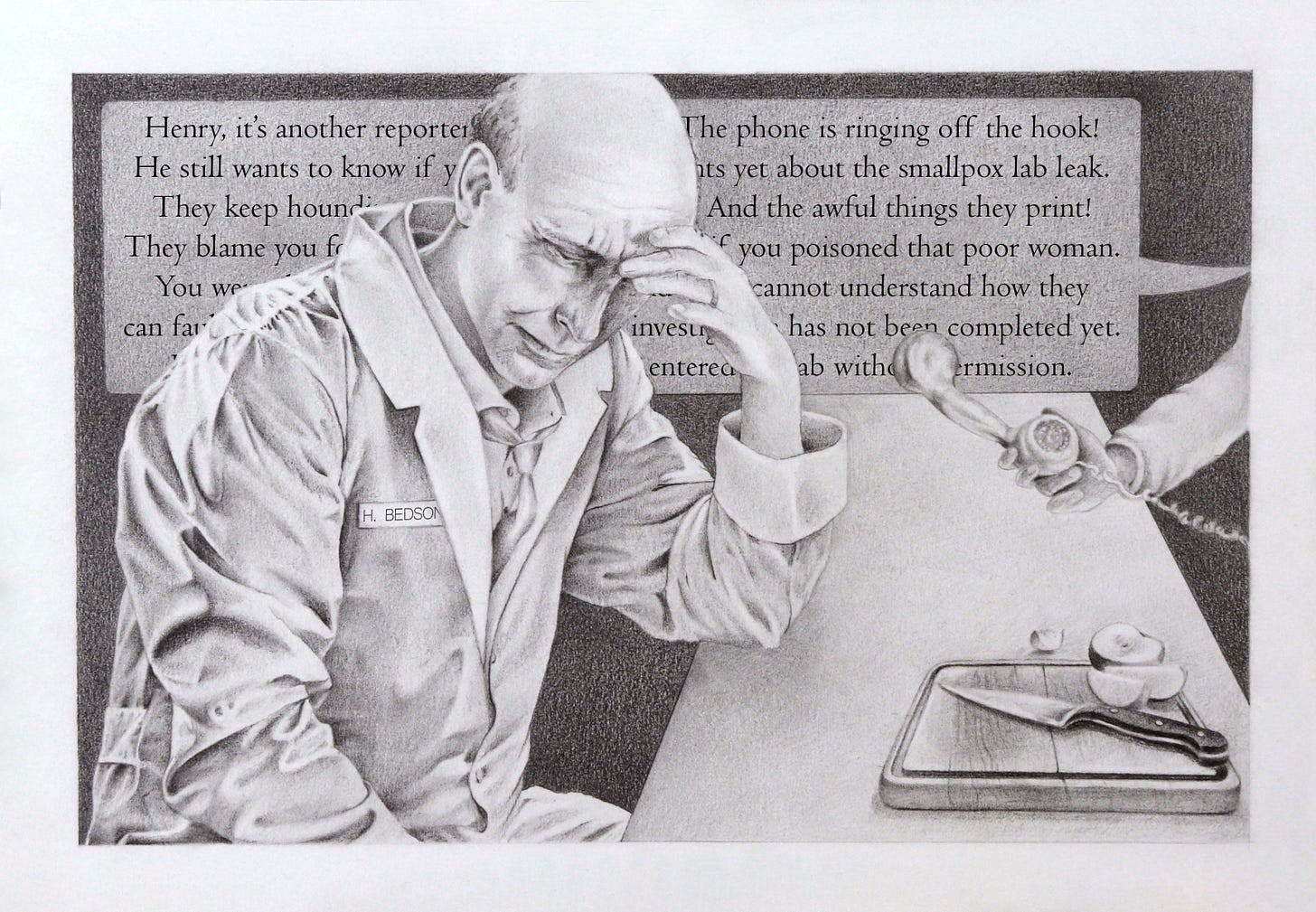

Few pathogens inspire fear like smallpox. In 1978, the last smallpox victim caught the disease from a laboratory in Birmingham, England. There was a “last” smallpox victim because scientists figured out how to eradicate that most gruesome virus, and today, smallpox only exists as laboratory specimens. Steven Pinker wrote about this accomplishment in Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress:

As a psycholinguist who once wrote an entire book on the past tense, I can single out my favorite example in the history of the English language. It comes from the first sentence of a Wikipedia entry:

“Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by either of two virus variants, Variola major and Variola minor.”

Yes, “smallpox was.”

If smallpox victims didn’t hemorrhage to death, they were permanently disfigured by pitted scars and sometimes left blind. Perhaps no other scientific accomplishment more tangibly alleviated human suffering than the vaccination campaign that eliminated smallpox, a disease that killed half a billion people in just its last hundred years afflicting us.2

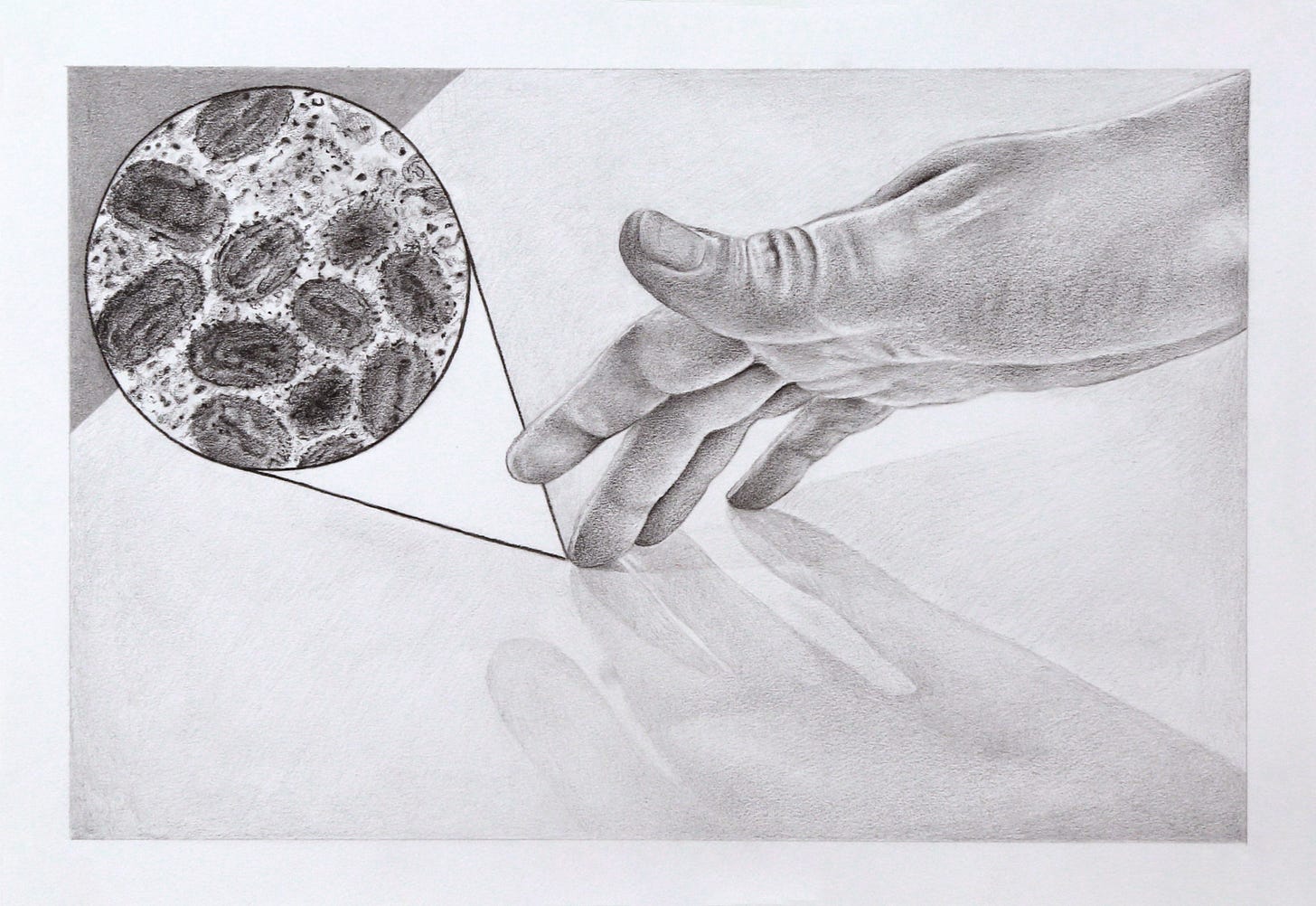

And yet, that very same scientific research exposed a medical photographer named Janet Parker, who worked above a smallpox lab at the University of Birmingham Medical School, to the deadliest smallpox strain. Over the course of a month, her body was consumed by pustules that coalesced into large, confluent masses on her face that blinded her as she succumbed to a lonely death. With humanity poised to declare victory over smallpox, Birmingham was sent into a panic at its sudden reemergence.

Humanity’s triumph over smallpox cannot be undone by the suffering of a single woman. (Or even the two other deaths and eighty infections caused by smallpox lab leaks in the UK during the ‘60s and ‘70s.) But such accidental sacrifices show us that even the most valuable science has come at a cost, and that cost has been paid by bystanders. For people like me, whose love of science seems like reckless abandon to those with a more platonic relationship to the pursuit of knowledge, confronting this risk hurts. Considering how science can harm humanity makes me feel like a dog owner whose beloved pet — who would never hurt a fly! — suddenly rips a child’s face off.

The physicist Richard Feynman, who helped invent the nuclear bomb, reflected on this predicament in his 1955 speech about “The Value of Science”:

Scientific knowledge is an enabling power to do either good or bad — but it does not carry instructions on how to use it. Such power has evident value — even though the power may be negated by what one does.

I learned a way of expressing this common human problem [from] a proverb of the Buddhist religion: “To every man is given the key to the gates of heaven; the same key opens the gates of hell.”

…So it is evident that, in spite of the fact that science could produce enormous horror in the world, it is of value because it can produce something.

Perhaps virologists opened the gates of hell late in the year 2019; even so, scientists have opened the gates of heaven, too. As Pinker documented extensively in Enlightenment Now, science has fertilized human flourishing. He tells us, “We ought to use reason and science to enhance human well-being… The value of science is not the value of a bunch of people who call themselves scientists. It’s the concept. It’s also the value of science that tells us when there’s been a failure of reasoning, that identifies the biases and distortions and also points the way to overcome them.” It is in this spirit of admiration for science that we can probe whether the virologists implicated in the lab leak theory of COVID-19 origins have failed in their reasoning.

Within the field of infectious disease research, there may have been over a thousand lab leaks worldwide since humanity began studying pathogens in biosafety labs. Exact numbers are hard to come by, because meticulous and forthcoming records are unavailable globally. Not every incident of fumbled needles or spilled substances results in laboratory acquired infections. Headline-grabbing mishaps like Janet Parker’s illustrate the suffering that can result when they do.

Souped-Up Viruses

What’s worse is the benefits of some virology experiments are questionable.

A roiling debate over sketchy research began in late 2011 when Ron Fouchier conducted a “gain-of-function” experiment on the H5N1 avian influenza virus, a particularly nasty strain of the flu that is spread globally by migratory birds. He carried out this work in his laboratory at the Erasmus Medical Center in Rotterdam,3 the Netherlands, in collaboration with another team at the University of Wisconsin, Madison headed by Yoshihiro Kawaoka, with funding from the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH).

The NIH defines “gain-of-function” as “scientific research that increases the ability of any of these infectious agents to cause disease by enhancing its pathogenicity or by increasing its transmissibility among mammals by respiratory droplets.” Fouchier and his colleagues repeatedly infected ferrets with H5N1 influenza to encourage the virus to accumulate new mutations until they created an “airborne” version, so that the virus gained the function of spreading through the air to infect mammals. Ferrets were ideal test subjects to use as proxies for people, because they are sickened by the flu similarly to humans.

In a 2012 New York Times article on the controversial experiment, “Dr. Fouchier said he was surprised by how easy it was to change the virus into the very form that the world has been dreading.” The world dreads an H5N1 virus that readily infects mammals through the air because this strain of “bird flu” has killed more than half the humans it ever infected since its discovery in 1996 — this is an extraordinary mortality rate. But, H5N1 bird flu has thus far been unable to successfully transmit between humans, so infections have been limited to people with heightened exposure risk, such as poultry farmers.

H5N1 bird flu made headlines again earlier this year. The recent outbreak ratcheted up the price of eggs as poultry farms lost staggering amounts of birds to the disease. More alarmingly, a new strain began infecting minks in October 2022 at a fur farm in Spain, where it adapted the until-now unprecedented ability (outside of the labs in Rotterdam and Wisconsin) to readily spread from mink to mink, mammal to mammal. More than 50,000 mink at the fur farm were culled and their carcasses destroyed as workers were placed under quarantine restrictions. This past February, over 700 sea lions were found dead en masse with H5N1 infections across the shores of Peru.

So why would virologists intentionally enhance the pandemic potential of such a deadly flu virus? Some of Fouchier’s colleagues wondered the same. Spurred by this troubling experiment, concerned scientists gathered at the Royal Society of London in 2012 for the first major discussion about the value versus the risk of gain-of-function research. By July 2014, enough laboratory mishaps had come to light that a group of scientists formed the Cambridge Working Group to issue a statement calling for curtailing gain-of-function research on potential pandemic pathogens until a formal risk-benefit assessment could buoy safety. They introduced the problem forcefully (emphasis added):

Recent incidents involving smallpox, anthrax and bird flu in some of the top US laboratories remind us of the fallibility of even the most secure laboratories, reinforcing the urgent need for a thorough reassessment of biosafety. Such incidents have been accelerating and have been occurring on average over twice a week with regulated pathogens in academic and government labs across the country. An accidental infection with any pathogen is concerning. But accident risks with newly created “potential pandemic pathogens” raise grave new concerns. Laboratory creation of highly transmissible, novel strains of dangerous viruses, especially but not limited to influenza, poses substantially increased risks. An accidental infection in such a setting could trigger outbreaks that would be difficult or impossible to control. Historically, new strains of influenza, once they establish transmission in the human population, have infected a quarter or more of the world’s population within two years.

Some incidents that may have been front of mind for the Cambridge Working Group include: In 2013, at the University of Wisconsin (home to Fouchier’s collaborators in the infamous ferret experiment), a researcher accidentally punctured through a gloved hand with a needle containing H5N1 avian influenza; UW reported nine other incidents to the NIH between 2012 and 2014. In July 2014, the same month the Cambridge Working Group issued their statement, the CDC released a report about two incidents at their facilities that involved personnel exposed to potentially viable anthrax and cross-contamination of samples with H5N1. Also in July 2014, six vials of smallpox virus were discovered inside cardboard boxes unsecured in a corner of an FDA laboratory’s cold storage room in Bethesda, MD, where they had rested for decades unbeknownst to any current laboratory staff. Fortunately, none of these mishaps infected anyone with smallpox, anthrax, or ultra-deadly influenza.

To respond to the Cambridge Working Group, Fouchier and Kawaoka helped form an organization called Scientists for Science, a provocative name insinuating that scientists who disagreed with them were not for science. A Harvard epidemiologist who co-organized the Cambridge Working Group, Marc Lipsitch, described how “each group garnered the support of prominent scientists and others.” The group in favor of gain-of-function research announced that they are:

…confident that biomedical research on potentially dangerous pathogens can be performed safely and is essential for a comprehensive understanding of microbial disease pathogenesis, prevention and treatment. The results of such research are often unanticipated and accrue over time; therefore, risk-benefit analyses are difficult to assess accurately.

Debate over Fouchier’s research peaked in October 2014, when the NIH, which had helped fund the ferret experiment, announced it would “pause” funding on certain projects using influenza, MERS, or SARS viruses until the government could complete a “deliberative process” to assess the risks and benefits. In 2017, the NIH lifted its funding pause and replaced it with a framework for new oversight over risky research. To justify funding gain-of-function experiments on potential pandemic pathogens, the NIH argues that:

This research can help us understand the fundamental nature of human-pathogen interactions, assess the pandemic potential of emerging infectious agents such as viruses and inform public health and preparedness efforts, including surveillance and the development of vaccines and medical countermeasures. While such research is inherently risky and requires strict oversight, the risk of not doing this type of research and not being prepared for the next pandemic is also high.

The ferret experiment in 2011 taught us that H5N1 bird flu could become airborne in mammals; the mink farm outbreak in 2022 taught us the same. Although the gain-of-function experiment confirmed a great fear about H5N1 about ten years before Mother Nature would, that decade-long head start did not help humanity find new solutions to the H5N1 bird flu problem. Instead, we have alarming headlines about Peruvian beaches becoming mass graves for sea lions.

And when it comes to COVID-19, decades of gain-of-function research on coronaviruses failed to adequately prepare us for a pandemic that has disrupted and devastated humanity, racking up a global death toll of at least 6.96 million and counting. Instead, research into mRNA vaccine technology proved to be humanity’s greatest asset against our newest plague.

Given this storied past of alarming experiments and lab accidents, it is striking how suspicions that COVID-19 started in a lab have been slandered as a conspiracy theory. Historical context alone justifies wondering if this plague was not just a tragedy, but a mistake. The incongruity of it all was best captured by comedian Jon Stewart in a bit on The Late Show with Stephen Colbert:

I honestly mean this. I think we owe a great debt of gratitude to science. Science has, in many ways, helped ease the suffering of this pandemic… which was more than likely caused by science….

Oh my god, there’s a novel respiratory coronavirus overtaking Wuhan, China. What do we do? You know who we could ask? The Wuhan novel respiratory coronavirus lab. The disease is the same name as the lab! That’s just a little too weird, don’t you think? And then they ask the scientists… how did this happen? And they’re like, hmmm, a pangolin kissed a turtle?

…Okay, what about this! Oh my god! There’s been an outbreak of chocolatey goodness near Hershey, Pennsylvania. What do you think happened? Oh, I dunno, maybe a steam shovel mated with a cocoa bean… or, it’s the chocolate factory!

This is not a conspiracy. This is the problem with science. Science is incredible, but they don’t know when to stop. And nobody in the room with those cats ever goes, I don’t know if we should do that. They’re like, curiosity killed the cat, so let’s kill 10,000 cats to find out why. That’s what science does, they push things.

Of Leaks And Lawsuits

Jon Stewart’s pithy riposte raises the question: while studying coronaviruses, how far did virologists push things?

When the NIH paused gain-of-function funding, it granted some exceptions for ongoing projects, including experiments by three virologists who are now at the epicenter of COVID-19 lab leak allegations: Peter Daszak, the president of EcoHealth Alliance, a nonprofit organization that studies emerging infectious diseases; coronavirus expert Ralph Baric at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill; and Shi Zhengli, director of the Center for Emerging Infectious Diseases at the Wuhan Institute of Virology.

Daszak, Baric, and Shi have collaborated together on coronavirus research that reinvigorated the debate on gain-of-function experiments, such as a 2015 experiment of which Baric and Shi wrote, "Scientific review panels may deem similar studies… too risky to pursue," and that the scientific community was at “a crossroads of GOF research concerns; the potential to prepare for and mitigate future outbreaks must be weighed against the risk of creating more dangerous pathogens.”

The most controversial window into their collaboration comes from a grant proposal titled DEFUSE that Daszak, Baric, and Shi submitted in 2018 to the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), an arm of the U.S. Department of Defense. In it, they described plans to insert furin cleavage sites into bat coronaviruses with a high risk for spilling over into human populations, and then “infect humanized mice and assess capacity to cause SARS-like disease.” DARPA rejected their proposal. But when a research team called DRASTIC leaked it in September 2021, the revelation caused wide-spread alarm. An Atlantic article described why “There is good reason to believe the document is genuine,” and explained:

…the work described in the proposal fits so well into that narrative of a “gain-of-function experiment gone wrong” that some wondered if it might be too good to be true….

We’ve long known that the presence of such a site in SARS-CoV-2 increased its pathogenic power, and we also know that similar features have not been found in any other SARS-like coronavirus (though we may find them in the future)…. As the science journalist Nicholas Wade argued in an influential lab-leak-theory brief last spring, this genetic insertion “lies at the heart of the puzzle of where the virus came from.” The virologist David Baltimore even told Wade that the structure of the SARS-CoV-2 furin cleavage site was “the smoking gun for the origin of the virus.” (Baltimore later walked back his claim.)…

We don’t know whether that work was ever carried out — remember, DARPA rejected this proposal. Even if it had been, several experts told us, the genetic engineering would have happened at Ralph Baric’s lab in Chapel Hill... Yet now we know that the idea of inserting these sites was very much of interest to these research groups in the lead-up to the pandemic.

Long before DRASTIC leaked the DEFUSE proposal, the SARS-CoV-2 furin cleavage site was scrutinized by leading scientists the moment the pandemic began. The intensity of their investigation was not widely understood until unredacted records were grudgingly released through a lengthy Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) lawsuit. These records contained emails from early February 2020 between Anthony Fauci, then-director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID); Francis Collins, director of the NIH; leading virologists, including Ron Fouchier of the infamous ferret experiment; and a few scientists who would go on to write a wildly influential letter in the journal Nature Medicine titled “The Proximal Origin of SARS-CoV-2,” that became one of the most cited scientific letters ever written.

Choice quotes from those emails include Kristian Andersen of the Scripps Research Institute writing that he found “the genome inconsistent with expectations from evolutionary theory.” Robert Gary of Tulane University added, “I just can’t figure out how this gets accomplished in nature …it’s stunning.”4

“Surely that wouldn’t be done in a BSL-2 lab?” responded Collins, because biosafety level 2 labs have the equivalent safety profile of a dentist office. Another scientist reacted, “Wild West…” As the conversation continued, they discussed how serial passage in laboratory animals had previously resulted in the H5N1 bird flu virus attaining a furin cleavage site.

On February 8, 2020, Andersen wrote, “Our main work over the last couple of weeks has been focused on trying to disprove any type of lab theory, but we are at a crossroad where the scientific evidence isn’t conclusive enough to say that we have high confidence...” (emphasis original) This is the most inflammatory excerpt from their exchange. It exposes a scientist longing to pigeonhole reality, rather than dispassionately following the evidence wherever it may lead. Andersen was expressing “a conclusion in search of an argument,” in the words of David Relman, a professor of microbiology, immunology, and medicine at Stanford University, who has advised the U.S. government on emerging infectious disease threats, written about the need for more thorough investigations into the origins of COVID-19, and warned that lab leak risks in general must be taken more seriously.

Andersen and Gary helped pen the “Proximal Origin” letter that framed the global conversation by concluding, “our analyses clearly show that SARS-CoV-2 is not a laboratory construct or a purposefully manipulated construct,” and, “we do not believe that any type of laboratory-based scenario is plausible.” Their public certainty clashes with their private concerns.5

Last month, journalists at Public released the “Proximal Origin” authors’ private Slack messages, in which Andersen6 continued agonizing over the very real possibility that SARS-CoV-2 leaked from a lab about a month after publishing the widely acclaimed letter. In April 2020, Andersen wrote his colleagues, “But here’s the issue — I’m still not fully convinced that no culture was involved. If culture was involved, then the prior completely changes — because this could have happened with any random SARS-like CoV, of which there are very many. So are we absolutely certain that no culture could have been involved?” (emphasis original) This correspondence is even more intimate than the emails, offering an unvarnished record of what these scientists believed.

Andersen and his co-authors were initially stunned by the new virus because of structures like its furin cleavage site and its “unprecedented” ability to burn through human populations “like wildfire.” Anderson called the lab leak “so friggin’ likely to have happened.” They consciously searched for reasons to discount a lab leak scenario while scheming about how to deflect journalists so that the public would not worry about a lab leak, too.

After reading through the 140-page document, I believe that the “Proximal Origins” authors genuinely convinced themselves that a lab leak was unlikely. They never found the concrete proof of a natural origin that they were hoping for — a closely related virus with a furin cleavage site, or infected animals that had passed the virus onto humans — but they analyzed viruses more distantly related to SARS-CoV-2 that each shared this or that quality, and then decided that a lab leak was not absolutely necessary for explaining the strange, new virus. To their credit, they were frequently critical of Ron Fouchier, Peter Daszak, and other scientists who refused to accept that their research was risky or that lab leaks were worth worrying about, at one point even coming up with a cartooned image of Daszak that depicted him as a mad scientist.

Qualified experts disagree over how to interpret the strange qualities of SARS-CoV-2, and I lack the know-how to weigh in on that argument. But one need not be a scientist to see how desperate the “Proximal Origin” authors were to disabuse themselves of the lab leak theory. Witnessing such intense motivated reasoning saps me of confidence in their conclusions. They were afraid that a lab leak might be true. People who fear the truth cannot be taken at their word.

Similar to “Proximal Origin” in its impact on discrediting the lab leak theory, another widely influential letter was published in the medical journal The Lancet on February 19, 2020. The “Statement in support of the scientists, public health professionals, and medical professionals of China combatting COVID-19,” was signed by 27 prominent scientists who declared:

The rapid, open, and transparent sharing of data on this outbreak is now being threatened by rumours and misinformation around its origins. We stand together to strongly condemn conspiracy theories suggesting that COVID-19 does not have a natural origin… Conspiracy theories do nothing but create fear, rumours, and prejudice that jeopardise our global collaboration in the fight against this virus.

As with “Proximal Origin,” public facing statements in the Lancet letter were undermined by the private correspondences of its authors. When the nonprofit investigative public health group U.S. Right to Know obtained the authors’ emails in November 2020, it became known that Peter Daszak not only drafted the letter, but also attempted to obscure his and Ralph Baric’s authorship “to avoid the appearance of a political statement,” and “not be identifiable as coming from any one organization or person… simply a letter from leading scientists.” Daszak discouraged Baric and other EcoHealth-affiliated scientists from signing the letter to create “some distance from us” so that it “doesn’t work in a counterproductive way.” He said, “We’ll then put it out in a way that doesn’t link it back to our collaboration so we maximize an independent voice,” and Baric agreed, “Otherwise it looks self-serving, and we lose impact.” Although Daszak initially thought better of it, he ultimately signed the letter.

It took about six months for Daszak to finally disclose his conflicts of interest.7 As president of the EcoHealth Alliance, Daszak funded coronavirus research in Wuhan through substantial grant money he received from the NIH and then subcontracted to the Wuhan Institute of Virology.8 Science journalist Nicholas Wade pointed out in his comprehensive essay on the origins of COVID-19 that, “If the SARS2 virus had indeed escaped from research he funded, Dr. Daszak would be potentially culpable.”

A Nightmare of Circumstantial Evidence

At the time of this writing, fewer and fewer people are smearing the lab leak theory as conspiratorial.9

The FBI has long maintained that a lab leak is likely, and more recently, the Energy Department that oversees a network of U.S. laboratories agreed with the FBI, citing new intelligence that changed their official stance from undecided. Although most U.S. intelligence agencies do not lean towards the lab leak scenario, the Energy Department and FBI are the most qualified to evaluate the possibility. More to the point, the U.S. intelligence community is not treating the lab leak theory as a crackpot idea.

To be clear, the evidence for a lab leak is only circumstantial.10 And concrete proof is not forthcoming, because records from the Wuhan Institute of Virology have been sealed by the uncooperative Chinese government. When W. Ian Lipkin, a renowned professor of epidemiology at Columbia University, discussed the lab leak with “Proximal Origin” lead author Kristian Andersen in February 2020, he wrote that, “Given the scale of the bat CoV research pursued there and the site of emergence of the first human cases we have a nightmare of circumstantial evidence to assess.”11

Assessing this circumstantial evidence is beyond the scope of this essay. The context I’ve provided here is neither a comprehensive synopsis of the lab leak theory of COVID-19 origins, nor a careful comparison of its merits against the view that SARS-CoV-2 emerged naturally. Instead, this background information forms the bedrock of my analysis about why the lab leak theory has been disparaged.

Psychic Grief

Plenty of explanations can account for the desire to dismiss the lab leak theory. In the U.S., the issue was quickly politicized between Democrats and Republicans, and many pinpoint this polarization as the primary reason why the lab leak theory is controversial. President Trump’s detractors eagerly distanced themselves from his speculation about Chinese bioweapons. Even without that sinister spin on the Chinese Communist Party, it is uncontroversial that the CCP would have punished Chinese scientists for revealing anything about COVID-19 origins that the CCP did not want released. Perhaps those scientists’ colleagues outside China kept mum out of fear for their friends’ safety.

Silence could also protect the legacy of their own life’s work. Every virologist in the world would risk their job security if the global public turned vehemently against them. Funding for their research would likely become scarce. As Upton Sinclair put it, “It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends on his not understanding it.” Virology research does not come cheap.

Graver still, the scientists implicated in millions of deaths may balk at taking responsibility for that magnitude of mass manslaughter. While the official global death toll hovers just below 7 million, concerns about underreporting have fueled estimates up to 31.4 million and counting. This staggering number is on par with the amount of people killed by China’s Great Famine. That was both the largest famine and greatest man-made disaster in human history, caused by Chairman Mao forbidding private food production in service of his Stalinist ideology. Who among us wishes to compete with Chairman Mao in the category of “blithely causing untold numbers of slow and agonizing deaths?”

If any scientists knew that they were responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic, they may have acted like a driver who hit a motorcyclist then fled in a panic, leaving a battered body on the side of the road.

All of these explanations together easily explain the desire to dismiss the lab leak theory. But to this list, I would like to add another: we have never needed to take Dr. Frankenstein seriously until now. To me, at least, he had always seemed like a boogeyman embraced by anti-science reactionaries, to justify their thanklessness for the vast advantage science has bequeathed us.

In my capacity as something of a mad scientist, I believe that this rationale is the underlying cause — more so than even politicization, which set in after high profile scientists like the “Proximal Origin” and “Lancet” letter authors began working behind the scenes to control the conversation. And this helps explain why so many people who cannot be accused of having blood on their hands deny the lab leak possibility. For some of us who love science, taking its deathly downsides seriously may be too painful to face willingly.

Mad scientist tropes have been with us since the 1818 publication of Mary Shelley’s novel, but in the roughly two centuries since the science-experiment-gone-awry archetype entered the popular imagination, non-fiction examples have not fit it neatly. Our closest contender for a real-world Dr. Frankenstein has been J. Robert Oppenheimer, the “father of the atomic bomb,” whose successful detonation of the first nuke in 1945 reminded him of a line from Hindu scripture, “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.” But Oppenheimer had explicitly set out to apply scientific research towards military goals. The bomb itself was not an experiment-gone-awry, because it was designed for destruction. Better examples from the Manhattan Project are the fates of Harry Daghlian and Louis Slotin, two physicists who accidentally irradiated themselves while working with the same mass of plutonium nicknamed “the demon core” after their ghastly deaths by acute radiation syndrome.

Because nuclear fear has most conspicuously caused leeriness towards science, it has been my artistic focal point ever since I perturbed colleagues with my collection of uranium ore. For example, a physicist helped me dose daisy seeds with x-rays to mutate them like flowers found near the 2011 Fukushima meltdown. They were elongated like caterpillars. The misshapen daisies reminded me of Lyndon Johnson’s infamous 1964 campaign ad depicting a little girl counting daisy petals until a nuclear explosion engulfed the television screen; the cartoonish and childlike daisy is a potent symbol of innocence or — in this case — innocence corrupted. By mutating my own daisies, I hoped to channel these associations into art that evoked the tension between pursuing knowledge and curiosity killing the cat.

While the beautiful flowers were meant to attract, the knowledge of what I had done to them was meant to unsettle. I preserved my mutant blossoms in resin sculptures that were supposed to elicit contradictory emotions, like pleasure tinged with apprehension. Unlike a scientist intent on discovering how the world works, my artistic impulse was to learn how I could evoke emotional experiences — even elicit psychic grief if I could manage to touch someone’s mind that intimately.

But my own soul never felt too troubled, because I held immense hope that curiosity would not kill the cat. At any rate, it had nine lives, and a little acute radiation syndrome now and then was dwarfed by the immense boon science offered. Although I did take scientific risks seriously enough to fixate my fascination on them, I never thought that they justified curtailing scientific pursuits. On balance, I have always been enthusiastic about scientists’ track record. Steven Pinker’s thesis that Enlightenment values act like a solvent on human suffering forms a cornerstone of my own philosophy that curiosity is sacred.

And so, although I cannot peer into the hearts of scientists like Kristian Andersen, Peter Daszak, or Ron Fouchier, I can interrogate my own. I can imagine the thrill of creating microscopic Frankenstein’s monsters and marveling at my ability to invent new lifeforms. It would feel sublime. The awe would be addictive. To someone like me, the point of such research would not be practical goals like predicting and preventing the next pandemic (those would serve as mere justifications for grant money and public support), but rather the loftier goal of transcending the current limits of human understanding.

Although I clearly see the risks, I’m reluctant to fully condemn gain-of-function research, because I abhor the prospect of shutting a door to the unknown. Mysteries and marvels surely exist beyond that threshold! We cannot know what we would lose to that void of ignorance. I would readily relegate risky research to isolated islands, but I flinch at the safest option of banning it altogether. The unknown is such valuable territory.

The world should feel wary of people like me. Our craving for rapturous wonder can bowl over sensible concerns like keeping humanity’s best interests at heart.

It's easy for an artist who dabbles with science to fess up to these failings. Artists are supposed to be provocative. But we hold scientists to higher standards. The mad scientist clashes with a mantra that comforted many during the COVID-19 pandemic: “Trust the science.” We don’t just count on scientists to help us understand how the world works; we rely on them to teach us how to save lives.

When I try to empathize with the psychic grief scientists must feel when their mistakes take a life, I understand why Henry Bedson, the director of the Birmingham smallpox lab that infected Janet Parker in 1978, dealt himself the ultimate punishment.

The Value of Science

Virology may eclipse nuclear fear in its capacity to elicit horror and suspicion of the scientific enterprise. If the COVID-19 pandemic did begin in a laboratory, then for the first time since the Scientific Revolution began, humanity can credibly blame a scientific mishap for millions of deaths. What is the value of science if this turns out to be true?

To approach this troubling question like a math formula, we would tally up estimates of how scientific advancements have alleviated human suffering (such as eliminating smallpox) and then subtract estimates of how scientific mistakes have contributed to human suffering (such as Janet Parker’s death). But this is unsatisfactory because of unquantifiable “what ifs,” as in, “What if a future lab leak releases a pathogen that kills billions instead of millions?” Fear of the unknown animates the mad scientist trope: he plays god, but without heavenly omniscience he cannot predict the consequences.

What, then, is the value of science? The answer is that the value of science is the same as it ever was. Nothing has changed since Richard Feynman gave his 1955 speech and told us:

Scientific knowledge is a body of statements of varying degrees of certainty—some most unsure, some nearly sure, none absolutely certain… But I don’t know whether everyone realizes that this is true… Here lies a responsibility to society…

Our responsibility is to do what we can, learn what we can, improve the solutions and pass them on … In the impetuous youth of humanity, we can make grave errors that can stunt our growth for a long time. This we will do if we say we have the answers now, so young and ignorant; if we suppress all discussion, all criticism, saying, “This is it, boys, man is saved!” and thus doom man for a long time to the chains of authority, confined to the limits of our present imagination. It has been done so many times before.

It is our responsibility as scientists, knowing the great progress and great value of a satisfactory philosophy of ignorance, the great progress that is the fruit of freedom of thought, to proclaim the value of this freedom, to teach how doubt is not to be feared but welcomed and discussed, and to demand this freedom as our duty to all coming generations.

That is the idea Steven Pinker championed when he said, “The value of science is not the value of a bunch of people who call themselves scientists. It’s the concept.” No mad scientist (or global community of frightened virologists) can detract from this satisfactory philosophy of ignorance.

Indeed, it is those who strove so hard to squash doubt about COVID-19 origins that have acted against the scientific ethos. Their efforts – not the lab leak theory – are anti-science. They abdicated their responsibility to teach that doubt is not to be feared but welcomed and discussed.

One of the earliest lab leaks took place in 1903, when an assistant bacteriologist at the Minnesota State Board of Health was accidentally infected with a bacterial disease called glanders, which causes lesions and ulcerations, while performing an autopsy on a guineapig. A microbiologist at the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases also contracted glanders in 2000, possibly from handling live bacterial samples without gloves. Humanity has been studying germs for over a century now, and in that time, technological progress has not guaranteed lab safety.

This quantifiable impact may impress the value of science upon those immune to Carl Sagan’s romanticism when he swooned, “The cosmos is within us. We are made of star stuff. We are a way for the universe to know itself.” That scientific research and the technologies it inspired gave humanity the tools to eradicate smallpox should be “Exhibit A” in every argument against Luddites.

As a devoted Dune fan (spoiler alert), I’m struck that this laboratory shares its name with the artificial intelligence Erasmus, a character introduced in the prequel novels who helps invent a bioweapon plague against humanity, as well as performing other sick experiments in his own lab. Obviously, both the real-life lab and the AI are named after the Renaissance era Dutch philosopher and humanist.

Fauci wondered if the unusual features of SARS-CoV-2 could have been achieved through “serial passage in ACE2-transgenic mice.” This refers to mice genetically engineered to carry human lung cell receptors, like the ones used in Daszak, Baric, and Shi’s coronavirus experiments that the NIH exempted from the gain-of-function pause; such mice are used as substitutes for human bodies. “Serial passage” is the same technique Fouchier used in his ferret experiments, where lab animals are repeatedly infected by a virus to encourage a rapid accumulation of mutations.

”Proximal Origin” scientists claimed that they dismissed the lab leak theory after learning of reports that Chinese scientists may have found a virus extremely similar to SARS-CoV-2 in pangolins, a type of scaly anteater that is the most trafficked mammal in the world. If it could be demonstrated that an animal in close contact with humans had passed the virus on to us, then the lab leak theory would lose credence. The family of coronaviruses that include SARS, MERS, and SARS-CoV-2 originate in bats, which are the “natural reservoir” for SARS-like viruses. In the case of SARS, the bat coronavirus first infected palm civets, another heavily trafficked mammal, and MERS first infected domesticated camels. Those animals then incubated SARS and MERS until those coronaviruses mutated into forms able to infect the humans in close contact with them.

SARS broke out in the Guangdong Province of China in November 2002, and palm civets were determined to be its intermediate host with a high degree of certainty in October 2003 — the proximal origin of SARS was well understood within a year of the initial outbreak. A decade later, MERS emerged in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia in June 2012, and camels were determined to be its intermediate host with a high degree of certainty in August 2013 — the proximal origin of MERS was also well understood within a year of the initial outbreak. Given this track record, it was reasonable to assume that if SARS-CoV-2 also had an intermediate host, then it would be discovered sooner rather than later.

Those pangolin reports turned out to be insubstantial. The published data was shoddy, including misattributions, mislabeling of samples, and missing data, for which the journal Nature issued a correction about a year later; what reliable pangolin viral data we have come from animals confiscated from illegal traffickers in Guangdong Province in 2019 (where the first SARS virus emerged) almost 1,000 kilometers away from Wuhan (where SARS-CoV-2 emerged). Tellingly, neither pangolins nor bats were sold in Wuhan markets. Although more than 20 humans had close physical contact with the sick pangolins, none were infected by the pangolin coronaviruses. Subsequent analysis of commonalities between the pangolin viruses and SARS-CoV-2 found that the pangolin viruses were not similar enough to be considered ancestral strains of SARS-CoV-2.

To date, a little more than three years after the outbreak began, there is no known intermediate host for SARS-CoV-2.

Both the leaked Slack channel and emails written by Andersen during the peer review process for publishing “Proximal Origin” show that even before publication, the pangolin reports did not cause him to abandon the lab leak theory. He wrote, “Unfortunately, the newly available pangolin sequences do not elucidate the origin of SARS-CoV-2 or refute a lab origin… [T]here is no evidence on present data that the pangolin CoVs are directly related to the COVID-19 epidemic.”

Despite this, and although he was not credited as a co-author of “Proximal Origin,” Jeremy Farrar, now the Chief Scientist at the World Health Organization, emailed Andersen to apologize for “micro-managing” the letter. Farrar then asked him to change one sentence of the letter from, “It is unlikely that…” to, “It is improbable that SARS-CoV-2 emerged through laboratory manipulation of an existing SARS-related coronavirus.” Andersen agreed.

(Edit 8/31/23: To be more accurate, I changed “they” to “Andersen” in this sentence. I’ve been discussing the controversy with journalist Jamie Palmer of Quillette, who published a recent critique of the lab leak theory in that magazine. He rightly pointed out to me that the only “Proximal Origin” author to express doubts in the Slack channel in April 2020 was Andersen. Although I was aware of this, I initially wrote “they” because I was describing a conversation among multiple people, but upon reflection I agree with Palmer that specificity is necessary here. For an opposing perspective on the lab leak theory, please check out his essay. I disagree with his conclusions but believe it is worth a read.)

Soon after, The Telegraph reported in detail how, “All but one scientist who penned a letter in The Lancet dismissing the possibility that coronavirus could have come from a lab in Wuhan were linked to its Chinese researchers, their colleagues or funders,” and that since its publication, “several of those who signed the letters have since changed their stance.”

Richard Ebright, a molecular biologist and biosecurity expert who has vocally called for a transparent and thorough investigation into COVID-19 origins, described Daszak’s conflict of interest bluntly: “Daszak has been a contractor, a collaborator, and a co-author on work at the WIV [Wuhan Institute of Virology] on construction and analysis of novel chimeric coronaviruses.”

In May 2021, Ralph Baric joined critics of gain-of-function research like Marc Lipsitch, a co-organizer of the Cambridge Working Group; Alina Chan, a microbiologist and co-author of a book about COVID-19 origins; and David Relman, an expert on emerging infectious disease threats, in signing a letter published in Science that stated:

Theories of accidental release from a lab and zoonotic spillover both remain viable… Furthermore, the two theories were not given balanced consideration…

As scientists with relevant expertise, we agree with the WHO director general, the United States and 13 other countries, and the European Union that greater clarity about the origins of this pandemic is necessary and feasible to achieve. We must take hypotheses about both natural and laboratory spillovers seriously until we have sufficient data.

Anthony Fauci insists, “I have a completely open mind about [the theory that the virus may have leaked from a lab in China in 2019], despite people saying that I don’t.” President Biden asked the U.S. intelligence community to conduct investigations into the origins of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“There is no smoking gun proving a laboratory origin hypothesis, but the growing body of circumstantial evidence suggests a gun that is at very least warm to the touch,” said Jamie Metzl, who has served as an expert on human genome editing for the WHO, in his testimony at the first House subcommittee hearing on COVID-19 origins.

Here are just three examples of the circumstantial evidence for the lab leak theory:

First, in 2018, U.S. State Department inspectors voiced their alarm about the Wuhan Institute of Virology in a cable to Washington, “The new lab has a serious shortage of appropriately trained technicians and investigators needed to safely operate this high-containment laboratory.” One U.S. official described that cable as “a warning shot… begging people to pay attention to what was going on.”

Second, the closest known relatives to SARS-CoV-2 were found in bats caves in Yunnan, about 1,500 kilometers away from where the outbreak began in Wuhan. Two pathways have been identified as the likeliest routes for the virus to make its way from distant Yunnan to Wuhan: infected, intermediate host animals sold at a market in Wuhan, or scientists who collected viral samples from bat caves in Yunnan to bring back to the Wuhan Institute of Virology for research.

Research teams led by Shi Zhengli intensely sampled thousands of bats in Yunnan for coronaviruses and brought those viral samples back to the Wuhan Institute of Virology. When the COVID-19 pandemic began, Shi famously said, “I had never expected this kind of thing to happen in Wuhan, in central China,” because her team had never found SARS-like viruses in central China and instead had to travel far from Wuhan to collect samples, and so she wondered, “Could they have come from our lab?” A profile of Shi in Scientific American described how “she frantically went through her own lab’s records from the past few years to check for any mishandling of experimental materials, especially during disposal. Shi breathed a sigh of relief when the results came back: none of the sequences matched those of the viruses her team had sampled from bat caves. ‘That really took a load off my mind,’ she says. ‘I had not slept a wink for days.’”

But the earliest recorded case of COVID-19 was a patient who fell ill on December 1, 2019, and who had no connection to the Wuhan market. (Edit 8/31/23: I came across this explainer by virologist Jesse Bloom about the limits of what we know about early cases.) Of the documented early cases, 13 out of 41 had no link to the market. Daniel Lucey, an infectious disease specialist at Georgetown University, commented, “That’s a big number, 13, with no link.” Animals in and around Wuhan were tested for SARS-CoV-2, but zero infected animals were found; all traces of SARS-CoV-2 in the Wuhan market were environmental samples consistent with what we would expect to find if large numbers of infected people contaminated surfaces while visiting. This could mean that the market was home to the first COVID-19 superspreader event, rather than the beginning of the outbreak.

Notably, the “Proximal Origin” authors repeatedly dismissed the market as a likely origin source in their leaked Slack channel for these reasons and more.

That Scientific American interview with Shi noted that “scientists suspect that the pathogen might have been around for weeks or even months before severe cases raised the alarm.” This directly ties into the third piece of circumstantial evidence: in November 2019, weeks before severe cases raised the alarm, several researcher inside the Wuhan Institute of Virology became sick. As anyone who has earnestly awaited the results of a COVID-19 test knows, the same symptoms are also consistent with other cold and flu viruses, but alarmingly, all three researchers fell sick within a week of each other with severe symptoms that required hospitalization.

This nightmare of circumstantial evidence shows that dismissive statements — “The idea that this virus escaped from a lab is just pure baloney. It’s simply not true,” insisted Daszak in an April 2020 interview — ought themselves be spurned as risible.

The “natural origins” theory can only rally circumstantial evidence, too. On March 16, The Atlantic broke a story headlined “The Strongest Evidence Yet That an Animal Started the Pandemic” featuring interviews with “Proximal Origin” authors Kristian Andersen and Edward Holmes, along with other scientists who have vehemently denied the possibility of a lab leak. They attained brief access to Chinese data that the WHO described as corroborating, “Historical photographic evidence… that shows raccoon dogs and other animals were sold at these specific stalls [in the Wuhan market] in the past. Although this does not provide conclusive evidence as to the intermediate host or origins of the virus, the data provide further evidence of the presence of susceptible animals at the market that may have been a source of human infections.”

When Andersen was interviewed for The Atlantic, “He underscored that the findings, although an important addition, are not ‘direct evidence of infected raccoon dogs at the market… Do I believe there were infected animals at the market? Yes, I do.’” However, the WHO maintains that the data offers no definitive answer about how the COVID-19 pandemic began. Given Andersen and his colleagues’ track record of expressing conclusions in search of arguments, the media blitz triggered by The Atlantic story may be more hype than substance.

Furthermore, after reading Andersen and his “Proximal Origin” co-authors dismiss the market as the pandemic origin in their Slack channel, I wonder if he has nagging doubts about this “strongest evidence yet.” If so, he may feel reluctant to write them down anywhere sleuths may find them.

(Edit 8/31/23: A peer-reviewed analysis of the data that triggered media hype about racoon dogs was recently published in Virus Evolution by virologist Jesse Bloom, in which he finds that genetic material from racoon dogs actually negatively correlate with SARS-CoV-2 material, and concludes, “These results suggest that SARS-CoV-2 was widespread in the market by January 2020 and therefore that co-mingling of viral and animal genetic material in environmental samples collected at that time is unlikely to be informative about the original source of the outbreak.”)

This was a wonderful read, thanks!

thanks for this great perspective and your diligent research into the topic!

so important that non-scientists understand the risks involved in this research, the cover up of this accident, and that we really need to regulate this insanely risky research.

i well remember being at the receiving end of all the insults and heavily constructed, illogical counterarguments coming from virologists like andersen. they didn't like our preprint...

felt so weird to read that he also looked at the FCS and restriction site pattern and concluded a lab accident to be highly likely, just like us, but then published the opposit.

just in case you want to look further into the molecular origin evidence, this is the talk i gave on the matter: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EuuY94tsbls