On Claire Lehmann’s “Feelings, Facts, and Our Crisis of Truth”

An idea worth drawing for.

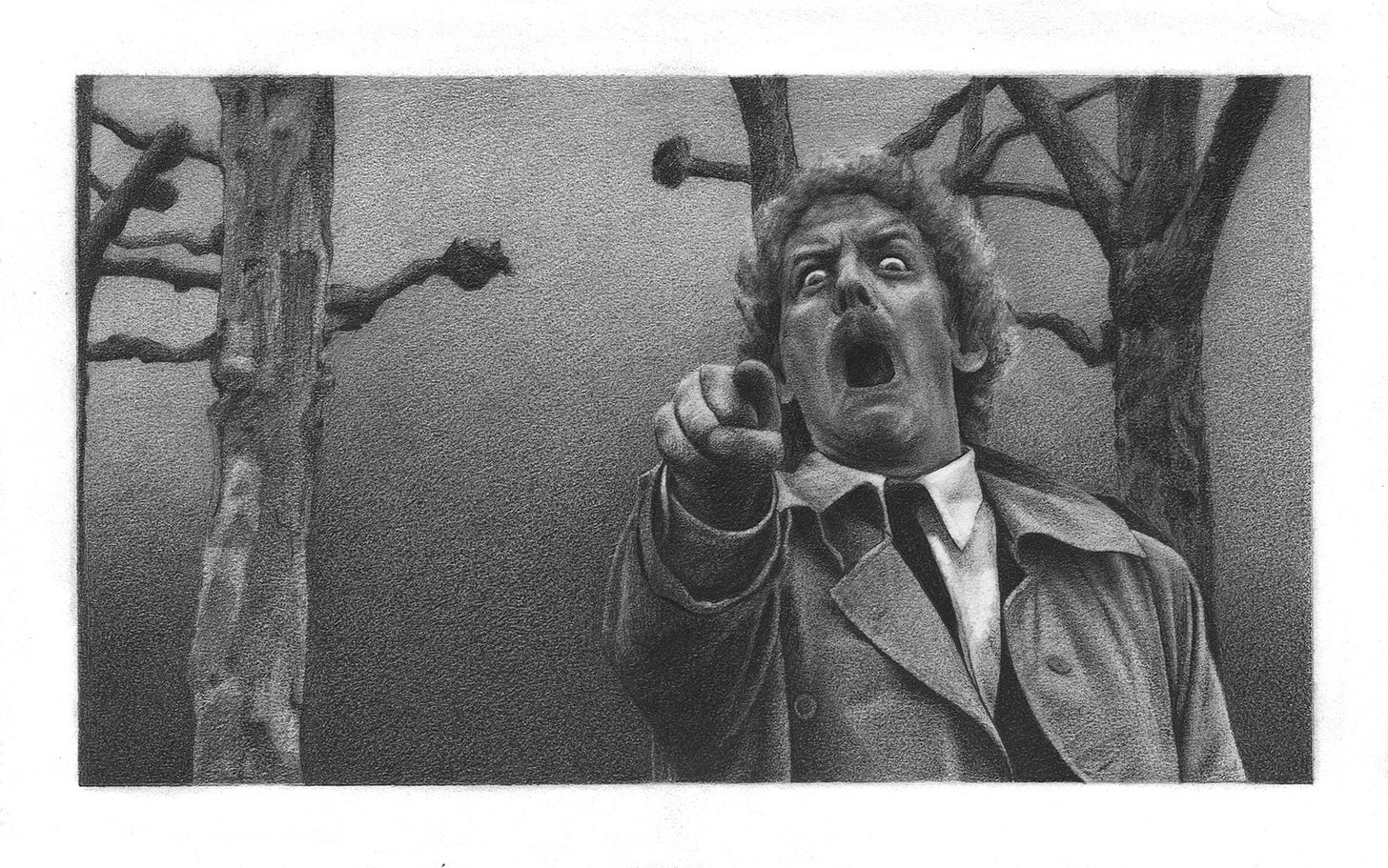

This visual essay is a tribute to Claire Lehmann. It’s part of an ongoing series called Ideas Worth Drawing For, in which I make hand-drawn images to honor the excellence of essayists I admire.

We seem to have transitioned from Postmodernism to Post-Truth. Back in 2016, Oxford Dictionaries proclaimed “post-truth” the Word of the Year, defining it as “relating to or denoting circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion or personal belief,” and explaining that the concept became ascendent “in the context of the Brexit referendum in the UK and the presidential election in the US, and becoming associated overwhelmingly with a particular noun, in the phrase post-truth politics.” Oxford Dictionaries goes on to clarify that in this usage, the prefix “post-” is not “simply referring to the time after a specified situation or event” but instead “has a meaning more like ‘belonging to a time in which the specified concept has become unimportant or irrelevant,’” akin to comedian Stephen Colbert’s more playful synonym, truthiness.

For those of us who believe that the world is ultimately knowable, however difficult the learning curve, our Post-Truth Era is a frustrating escalation from Postmodernism. As Claire Lehmann, the founding editor of Quillette, wrote in her recent essay for The Dispatch “Feelings, Facts, and Our Crisis of Truth”:

Since the mid-20th century, many elite institutions have rejected the philosophical orientation of empiricism in favor of a faddish postmodern view of the world. Postmodernism, alongside romanticist and fundamentalist religious modes of thought, rejects the notion that humans are able to discern what is true through data collection and experimentation. Romanticists believe that the truth is discerned through feeling, fundamentalists through revelation—and postmodernists believe that there is no such thing as truth at all. Our new media ecosystem blends all three of these outlooks, rendering empiricism a quaint relic of another age.

A core facet of the Post-Truth Era is an expansion of the quip “Some ideas are so absurd that only intellectuals believe them"1 to a generalized hostility towards elites and expertise. And while there are certainly intellectuals who have embarrassed themselves by embracing nonsense, the same is true of every type of person,2 and the only solution is more intellectual rigor—the very quality that creates experts. Lehmann offers the example of Bret Weinstein, an evolutionary-biologist-turned-podcaster, as someone who has been rewarded for renouncing expertise in favor of conspiracy theories:

Weinstein has suggested that Israel’s unpreparedness for the October 7 attack was deliberately orchestrated by powerful interests to create division among COVID skeptics; China’s one-child policy was strategically designed to create an army of males to infiltrate the U.S. military; and that his own groundbreaking telomere research was stolen by one of his peers—who went on to win a Nobel Prize.

The continuous positive feedback from a growing audience doesn’t just reward methodological shortcuts—it demands them. There is no clearer demonstration of how audience capture drives counter-Enlightenment thinking in digital media than Weinstein’s trajectory. Rigor dampens engagement, and uncertainty saps attention. The marketplace of ideas has been subsumed by a marketplace of emotions, where incentives reward those with the sloppiest procedures.

And living in the age of “do your own research” can have deadly consequences for people who are bad at doing research. Lehmann begins her essay with this sad example:

An outbreak of measles—a disease once declared eliminated in the U.S.—has hospitalized 91 people in Texas, killing two unvaccinated school-aged children. It is a horrific disease: In severe cases, a child’s immune system collapses, and they suffer seizures and brain damage from encephalitis or drown as fluid fills their lungs.

And any outbreak of measles is entirely preventable. The first vaccine was introduced 62 years ago, and vaccination saved an estimated 60 million lives between 2000 and 2023 alone. Measles epidemics once represented a public health crisis, but today the disease represents a different kind of affliction—one that is both psychological and cultural in nature, and one that is surprisingly resistant to intervention.

This cynicism about expertise is exacerbated by the arms race between truth and lies—most recently enhanced by artificial intelligence. On the one hand, AI assistants can help those who genuinely seek the truth by collating vast amounts of information. This gives the writer and neuroscientist Erik Hoel hope that AI can bring polymaths back from the dead, if it can help generalists absorb the cavernous knowledge of myriad specialists. But then again, seeing is no longer believing in an age of generative AI. Posts on X are filled with plaintive calls to Grok, “Is this true? What is real?”

But this is just a technological upgrade to a familiar problem: Dishonesty has always enjoyed an advantage from fighting dirty. As I wrote in my last Ideas Worth Drawing For about Richard Hanania’s “Why the Media is Honest and Good”:

Perhaps an underlying problem with misinformation is that the solution is so boring. Hanania recommends that people be mindful of bias when they read the media and take time to listen to opposing views—bland stuff …

Even as technology evolves, the same staid advice applies to the pursuit of truth. Whether the media is duking it out over newspaper subscriptions in 1898, or vying to dominate the 24-hour news cycle in 1991, or scheming to addict you to social media algorithms in 2016, savvy readers are mindful of bias and take time to listen to opposing views. Photographic or video evidence may become meaningless in the age of artificial intelligence, but only because thoughtful people refuse to accept simulacra as their reality when they care about what’s real. We have yet to enter a period of history when someone genuinely determined to find the truth can’t make some progress toward that goal, however much the accumulation of knowledge in any given domain may ebb and flow. The conventional advice to be mindful of bias and listen to opposing views is so reliable as to become monotonous.

In principle, there’s nothing wrong with “doing your own research” if that entails finding credible experts and understanding their limitations—and most importantly, recognizing your own limitations as a layperson aspiring to comprehend a complex subject. When laypeople first wade into complexity, they need heuristics to help narrow the field of potential honest brokers. In my latest essay for Quillette, I wrote about one such heuristic: Look for people who are willing to criticize their own side of an argument, because that indicates they are probably principled rather than partisan.

This standard should be combined with another heuristic courtesy of The Dispatch co-founder Jonah Goldberg: Look for people who can survive the invasion of the body snatchers.

Back in March 2016—just a couple months before Oxford Dictionaries noted that the word “post-truth” exploded in frequency of usage—Goldberg complained in the pages of the storied conservative magazine National Review about the way American conservatives were succumbing to Trumpian populism:

At times, I sometimes think I’m living in a weird remake of The Invasion of the Body Snatchers. If you’ve seen any of the umpteen versions, you know the pattern. Someone you know or love goes to sleep one night and appears the next day to be the exact same person you always knew.

Except.

Except they’re different, somehow. They talk funny. They don’t care about the same things they used to. It’s almost like they became Canadian overnight—seemingly normal, but off in some way. Even once-friendly dogs start barking at them. I live in constant fear that I will run into Kevin Williamson, Charlie Cooke, or Rich Lowry and they will start telling me that Donald Trump is a serious person because he’s tapping into this or he’s willing to say that. I imagine my dog suddenly barking at them uncontrollably. …

I’ll say, “I’m sorry Rich, I don’t know what got into her.”

And I can just hear the Lowry-doppelganger replying, “When Mr. Trump is president, dogs will behave or they will pay a price. Just like Paul Ryan and Michelle Fields.”

“Lowry you bastard! You went to sleep! Why!? You went to sleep and now you’re gone!”

In a 2021 Vanity Fair interview Goldberg added, “People would go to sleep violently opposed to Trump and everything he represented, but by morning they’d start telling me how under comrade Trump, we were going to have the greatest harvest we’ve ever seen.” For Goldberg, a conservative intellectual born into a family of conservative intellectuals, this invasion of the body snatchers fractured his friendships and his career. But it also separated the wheat from the chaff by revealing who was willing to pay the social cost of maintaining their principles. While it is of course true that people may change their minds about ideological commitments, Goldberg was describing “a kind of crowd-sourced brainwashing” that “spread across the land like a wet rolling fog”—not intellectual growth. The invasion of the body snatchers is an extreme form of peer pressure or social contagion, against which survivors demonstrate true conviction.

Both aforementioned heuristics are about identifying who can resist assimilation into groupthink, and they overlap. People willing to criticize their own side of an argument may take that stand from within the madness of crowds. But the invasion of the body snatchers heuristic is distinct from the criticizing one’s own side heuristic. Defined simply, the body-snatched have hopped on a bandwagon that nullifies once strongly-held principles, without offering a coherent explanation for their change of heart.

In my Quillette piece about the criticizing one’s own side heuristic, I argue that we should all read Israeli historian Benny Morris because he passes that test masterfully. As I wrote, “perhaps no other topic inflames tempers and attracts propaganda merchants as much as the twinned fates of Israel and Palestine. It is hard to find information on the subject that is uncontaminated by prejudice.” Because that debate has so thoroughly muddled the truth, it offers an excellent case study for how we can apply the body snatchers heuristic:

Consider the case of Palestinian activist Mahmoud Khalil, who was detained by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) on March 8. The government has not pressed criminal charges against Khalil, a green card holder married to an American who gave birth to their first child last month in New York, whom he has not met because he is still imprisoned in LaSalle Detention Center in Louisiana. The Free Press reported on March 10 that a White House official said that:

Khalil is a “threat to the foreign policy and national security interests of the United States,” said the official, noting that this calculation was the driving force behind the arrest. “The allegation here is not that he was breaking the law,” said the official.

“He was mobilizing support for Hamas and spreading antisemitism in a way that is contrary to the foreign policy of the U.S.,” said the official, noting the Trump administration reviewed intelligence that found Khalil was a national security risk.

Also on March 10, The Weekly Dish writer Andrew Sullivan bemoaned that “looking around the web today, so many of my usual free speech supporters are quiet.” Then he began calling out The Free Press for their coverage. Though only a couple of days had passed since Khalil was detained, 48 hours is enough time for their robust newsroom to delve into an event that involves two of the biggest preoccupations at The Free Press: defending Israel and free speech—so that hateful speech towards Israel becomes a litmus test for whether The Free Press can be body snatched regarding free speech principles.

Could the Khalil case make some Free Press journalists feel as if their values are in tension?3 Their news story quoted above includes comments from people both condemning and supporting Khalil’s arrest, and it is reporting rather than editorializing. But Sullivan noticed that their only other comment was to post a video of Free Press staffer Maya Sulkin making dubious claims in a Fox News segment that Khalil is responsible for violent crimes because he handed out pro-Hamas pamphlets, compelling Sullivan to accuse The Free Press of placing “a massive asterisk next to the First Amendment.”

Notably, Sullivan criticized The Free Press as a friend to the newspaper’s founder, Bari Weiss, who had published Sullivan’s essay “How Many Children Is Israel Willing to Kill?” in January 2024 with this introduction:

Andrew Sullivan is one of this country’s great independent thinkers. He’s allergic to tribalism and groupthink, perhaps because, as a gay Catholic and a conservative who makes the case for liberalism better than most liberals, he doesn’t really belong in any one tribe. This is part of what makes Andrew such an interesting and important writer.

Andrew’s also a friend. A friend I often disagree with on a subject that matters a great deal to me: Israel.

So Sullivan knows that Weiss and her newspaper have been willing to hear out criticisms of Israel before. But he also knows that The Free Press had previously been quicker to defend free speech, and wondered aloud if anyone could give him an example of “another free speech issue where they haven’t taken a stand?” He seemed to worry that they had succumbed to the body snatchers, who “don’t care about the same things they used to,” as Goldberg described.

Throughout the month of March, Sullivan harped on The Free Press to uphold their free speech principles in a series of Substack notes:

By the end of the month, the editorial board at The Free Press finally put out a strong defense of free speech in their statement “No Deportations Without Due Process.” ICE had also arrested Rumeysa Ozturk, a Turkish graduate student and Fulbright scholar who had done nothing more than write an op-ed—unlike Khalil, no one is insinuating she is responsible for campus protest violence—and while The Free Press editors focus on her more sympathetic case, they do not forget Khalil either:

Due process is not a privilege for the guilty. It is a protection for the innocent. It is a hedge against the prospect that sometimes the state gets it wrong.

It may turn out that Ozturk and Khalil have coordinated their activism with Hamas, or encouraged or participated in riots or other activities that are more than sufficient grounds to expel them from the country. But the government should present the specific evidence against them in a court of law and also—crucially—in the court of public opinion. In other words, the burden of proof is on the government, and they’ve so far failed to provide sufficient evidence to justify their actions.

Sullivan celebrated:

In the end, The Free Press was not body snatched. And now, when their readers apply heuristics to gauge credibility, they’ll find that Weiss and her colleagues ultimately summoned the courage to defend their ideological opponents against a miscarriage of justice. Resisting temptation can be more admirable than having never been tempted, because it’s harder than innocence.

On the other hand, the temptation of The Free Press played out in parallel with a controversy at the University of Austin (UATX); both institutions share some of the same leaders, with Weiss on the UATX Board of Trustees alongside historian and UATX co-founder Niall Ferguson, who is also a columnist at The Free Press. While the newspaper and university are distinct entities, this overlap in leadership offers more insight into how Weiss and her colleagues grapple with the body snatchers. Last week, Quillette broke the story “Is the University Of Austin Betraying Its Founding Principles?” by Ellie Avishai, who co-founded a thriving affiliate institute at UATX that was abruptly cancelled because a donor took offense at Avishai tweeting that “We can have criticisms of DEI without wanting to tear down the whole concept of diversity and inclusion”:

If UATX officials want to prevent their school from operating merely as a high-concept redoubt for conservative culture warriors, they should re-commit to the school’s own founding principles, and leave the vitriolic “anti-wokeness” fusillades to podcasters and YouTubers. The school must be unwavering in its commitment to free inquiry, and show itself to be a welcoming home to a diversity of views, not just those that fall within a range acceptable to its biggest funders and most influential administrators.

Just as it was necessary for The Free Press editorial board to take a stand on the Khalil case, it would behoove Weiss to publicly address the UATX controversy.4 Though the latter is far less severe than the U.S. government abusing its power, both events reveal clues about how much someone values free thought. It’s reasonable for Free Press readers who apply the body snatchers heuristic to wonder about the implications of the UATX controversy for the newspaper’s founding editor.

But heuristics can only take you so far, because they are shortcuts for beginning to understand. Discerning credibility is but a starting point. In her essay about our crisis of truth, Lehmann diagnoses a key cause of the epistemic spasms in our Post-Truth Era:

On a recent episode of the Joe Rogan Experience, British author Douglas Murray challenged the world’s most popular podcaster over his penchant for hosting “armchair experts” who promote ideas outside of the mainstream. Specifically, Murray cited Rogan’s interviews with Daryl Cooper, a podcaster who has argued that Winston Churchill was the “real villain” of World War II, and comedian Dave Smith, who appeared on the podcast with Murray, and whose taste for criticizing Israel has never inspired him to pay a visit. Murray faced significant backlash from right-wing influencers on social media, while writers at The Atlantic, UnHerd, and Quillette rallied behind him. Yet despite the lengthy conversation, which spanned hours, some crucial concepts were left unaddressed.

The main issue that Murray did not raise was that in the ecosystem that Rogan occupies, many podcasters and their listeners do not read. Murray brought his norms of journalistic rigor into a largely postliterate culture, where information is consumed via aural and visual formats as opposed to the written word. It was a clash of cultures between an author and journalist who primarily lives in the world of printed text, and those who primarily live in the world of conversation and storytelling.

Long ago, when the arms race between truth and lies was just beginning, the invention of literacy made the truth durable. Of course, lies would also propagate and persist within the written word. But Lehmann explains how long-form texts uniquely benefit knowledge accumulation and accuracy:

This postliterate shift isn’t merely occurring in digital media ecosystems—it has penetrated some of the world’s most prestigious educational institutions. In an article for The Atlantic last year, Rose Horowitch described students at elite universities who struggle to read an entire book. One first-year student confessed she had never been assigned a complete book throughout high school—only excerpts and articles.

It’s important to distinguish the difference between a literate and postliterate world. For centuries, women died in childbirth at relatively steady rates. Only when doctors started sharing knowledge about obstetric techniques in medical journals did mortality rates start to decline. Sharing knowledge via the written word enhances the accuracy of the transmitted information, whereas oral reinterpretations lend themselves to inefficiency and error.

When an audio-visual narrative culture—which lacks the precision and permanence of written documentation—combines with amateur methods, our collective ability to discern the truth simply deteriorates.

But some bookworms are starting to see glimmers of hope. Last week, Henry Oliver published an optimistic piece in his literature newsletter The Common Reader explaining why he thinks that “Literature is so back.” He has started noticing that everyone around him seems to be reading the classics, including house painters blasting the Middlemarch audiobook, a novel that also went viral on Substack recently:

Look around Substack. We have so much energy here for all forms of literature, from science fiction to the Mahābhārata. So much of the enthusiasm I see about literature (on social media and in my WhatsApp), is from people in science, economics, and technology. Reddit is full of people reading the classics. 4chan too.

There are articles in the Guardian about spending less time with Twitter and more time with Jane Austen. Libby is showing strong numbers. Classic novels are selling well thanks to TikTok and fancy new editions.

Who knows why this is happening? … maybe we’re taking literature seriously because the times are complicated. We need humanism to help us see things clearly now. … We might be starting from a low point, but the literary recovery has begun. In a world of chaos and slop, the best stands out.

Hopefully Americans are embracing this nascent trend. As Lehmann points out, “The United States, a country founded on Enlightenment ideals, is at a crossroads”:

Trade policy is conducted according to vibes, anti-vaccine propaganda is spread by the highest health official of the land, and children now die of a once-eliminated disease. A path forward requires a counter-counter-Enlightenment. This doesn’t require censorship or an appeal to authority, but a return to rigor and the written word. While podcasts and videos are undoubtedly entertaining, their ability to transmit knowledge is time-consuming and inefficient. They are the equivalent of the fireside yarn—what humans did before we emerged from our caves. Text may not be as popular as a three-hour podcast conversation, but it remains the form of knowledge most likely to be accessed by future generations. Principia Mathematica was not a podcast, and On the Origins of Species was not a video series. Technologies may continue to create disruption, but we won’t enter a new Dark Age unless we forget the ability to read and write.

Maybe bookworms can seize American culture with our own invasion of the body snatchers. Oliver recalled the 1940 trend of people reading War and Peace everywhere, “On the bus. In restaurants at lunch. People were taking Tolstoy wherever they went.” After all, social contagion can cut both ways.

A podcaster may go to sleep one night and appear the next day to be the exact same person his audience always knew.

Except.

Except he’s different, somehow. He talks funny. He doesn’t care about the same conspiracy theories that he used to. It’s almost like he developed a hankering for Middlemarch overnight—seemingly normal, but off in some way. Even once-friendly dogs start barking at his podcast recording.

A podcast listener will say, “I’m sorry, I don’t know what got into her.”

And the podcaster-doppelganger will reply, “After I finish Middlemarch, I think I’ll start reading Shakespeare’s Henriad.”

“You bastard! You went to sleep! Why!? You went to sleep and now you’re gone!”

This is a snappier version of what George Orwell wrote in “Notes on Nationalism” that “One has to belong to the intelligentsia to believe things like that: no ordinary man could be such a fool.”—and how most people remember the quote.

However, elites have an outsized ability to implement their absurd ideas relative to the population at large.

While there are obviously a range of opinions held by the many writers at The Free Press, this is true of nearly everyone who works there.

Sohrab Ahmari promptly resigned from the UATX board of advisors as a result.

Speaking of body snatchers (and mind and soul too) this essay is very much about such

http://www.awakeninthedream.com/articles/invasion-of-the-body-snatchers-comes-to-life

Lovely, smart piece with a startling and funny surprise ending. Thank you.

We need some similarly thoughtful writing now about the "rule of law" and "human rights", not all they're cracked up to be.